● 5.1. Stepping into the magic of facilitation

In their book ‘Unlocking the magic of facilitation[1]’, Sam Killermann and Meg Bolger, refer to facilitation as a ‘powerful wand that, in well-trained hands, can achieve wonderful, healthy, positive outcomes.’ Literally, according to the Cambridge dictionary, facilitation means ‘making things possible or easy’. In the context of youth work, a facilitator helps young people acquire new skills and knowledge; guides the group towards the pre-decided objectives; acts as mediator; supports and encourages young people to reach new potentials. Through various techniques, a facilitator encourages critical thinking, instigates interest in the subject matter, promotes powerful, inspirational learning and enhances the sharing of ideas, active participation and a sense of ownership of the learning process. The ultimate goal of facilitation is to provide a safe and nurturing space for personal development, growth and most importantly change, both at a personal and social level.

Facilitation vs. Teaching vs. Lecturing

During lecturing, the “lecturer” has almost absolute control over the experience and content of learning. The aim to pass knowledge to the learners. Trainees have little room for initiative and their participation in the learning process is minimal. Lecturing is useful when the group is big in number, there is a lot of content to cover in a limited timeframe and when the lecturer possesses some specific knowledge that is important for the group to gain. Lecturing concentrates primarily on knowledge and not on skills or attitudes.

Teaching allows learners to participate more actively in the learning process however it is still the teacher that holds most of the knowledge, thus the approach is more instructive. In teaching, there is still considerable time pressure, but there is also some flexibility so that the group can get involved in the learning process, at least to some extent. Differently to lecturing, teaching is done for or with the learner(s).

Facilitation brings a different approach altogether and allows learners to fully participate in the learning process. The facilitator is not ‘above’ the group, nor do they take the role of the ‘expert’. Instead they are on equal footing with the group and are part of the learning process themselves. Facilitation encourages interactive, experiential learning and provides the space for the group to take the lead role in defining and owning its learning process. In lieu of its interactive learning character, facilitation takes more time to achieve a learning goal. At times during facilitation, it may be deemed necessary at times to use “mini” lectures or more guided ‘teaching’, especially when some concepts need to be presented before asking for the feedback from the participants. ‘Lecturing’ and ‘teaching’ may also come in handy during a facilitative process when wrapping up an activity and after the debriefing has taken place, to allow for better consolidation of the knowledge.

Three main goals of facilitation

- To help the group move towards specific goals or outcomes, i.e. to get to something different that they hadn’t known or experienced before the workshop in terms of awareness, knowledge, conceptualization, skills, attitudes, behaviours etc.

- To create and lead the group process. Create opportunities for interaction and collaboration that will help people shift in a way that they might not be able to independently

- To create an environment where each individual person can actively participate in and contribute to the process.

To reach the above goals, the facilitator may interchange between different facilitation styles, including:

- A Directive style: giving information, being guiding and direct, providing clear instructions on how to do something, as for example: ‘This is how we will go about this activity’

- Delegating: assigning tasks, roles and functions to individuals in the group either during the entire course of the training or for specific activities

- Exploratory: asking questions, encouraging people to voice their experiences and thoughts, promoting group interaction and interactive learning, exploring feelings, concepts and ideas.

Skills of good facilitation.

A good facilitator:

- Listens more and speaks less. As Sam Killermann put it, ‘there aren’t many laws when it comes to groups of human beings but there is one that has never failed us: if you don’t talk, someone else will!’.

- Uses good communication skills: Pays attention to the group’s verbal and non-verbal cues and responds to them. Pays attention to their own verbal and non-verbal communication cues: they maintain an ‘alert’, fluctuating, energetic, non-monotonous tone of voice; an open body posture; good eye contact with all members of the group; practice active listening.

- ‘Reads’ the group, understands the overall vibe, pulse, energy and climate of the group and responds to what the group needs and where it needs to ‘go’. To do this, they pay attention to both verbal and non-verbal cues such as body language, degree of engagement/withdrawal, resistance, energy levels etc. Groups give various signs about what they need and where they are at: facilitators need to open to read these signs. Listening to the group also means that the facilitator trusts the latent wisdom of the group andtrusts the group’s process. Each group will define its own unique process, regardless of how homogenous it may be with another group and regardless of the subject matter at hand. Some groups want to focus on more rational, conceptual aspects, other groups concentrate more on exploring feelings, reactions and impact. Remaining present and open, a facilitator can “read” the group’s signals and follow them accordingly.

- Leads the group by following and being supportive of its process: a good facilitator acts as an equal and integral part of the group and does not behave as if they are above it. Even though they know more about the subject, this should not result in a power dynamic. A facilitator has a lot to learn from the group and this is a great opportunity for personal growth and development.

- Remains ‘in-tune’ with the group, has their antennas open and responds not only to the obvious but also to what lies between the lines. To do this, they need to rely on insight and instinct.

- Asks questions that contribute to and enhance learning and growth. For instance, the facilitator asks:

- Open-ended questions to encourage participation, the sharing of thoughts and feelings and to instigate critical thinking (what, how, why?)

- Probing questions to encourage a more in depth sharing and to help a better understanding of the perceptions and opinions of the group. “Can you tell us more about this?”, “Why is it important, do you think?” Etc.

- Clarifying questions : “Can you explain what you mean? , “If I understand correctly does that mean that ….?

- Reflection questions to encourage participants to rethink/re-evaluate their opinions and further explore their feelings – “How did you feel when…”, “What made an impression on you”, “If we look at this from a different angle, could we….?”

- Gauging questions: to “feel the room”, get a sense of where the group is at, what their intellectual level is, how they interpret various concepts and what their probable emotional reactions may be. For example, a gauging question could be “how would you define gender identity” and based on the complexity of the group’s explanation (e.g., “gender exists as a spectrum” vs. “gender is penises or vaginas”), the facilitator knows how to move forward.

- Challenging questions that lead to an alternative way of thinking and lead to another perspective. Sometimes playing devil’s advocate. “What if we look at this from this perspective…?, “Is it possible that an alternative to what you said might be true for some people? How so?”

- Guiding questions, used to come to a specific conclusion (i.e. how could ‘tolerance’ of diversity may not constitute real acceptance?’

- Does not impose their own personal opinions on the group. The most important thing is to create the space for the group to share and listen to different perspectives, engage in critical thinking and in a constructive dialogue. Encourages the expression of ALL opinions, even the ones they disagree with. Also, does not judge others about their views no matter how stereotypical as they may seem. Instead, they open up the space in the group, so these stereotypical views are challenged by the group itself.

- Leads with empathy: consciously pays attention to understand where the group is coming from, understands their perspective, ‘gets into their shoes’ and does not to judge them for their beliefs or opinions. Validates feelings and responds with sensitivity, acknowledging a person’s experience as simply that, their own unique experience. At times, the facilitator may need to respond with ‘strategic empathy’ to feelings of discomfort and the paradoxes or ambiguity that may surface during the discussion. This would mean to allow room for difficult or negative feelings to be explored (instead of shut out) so they can challenge preconceived notions, discriminatory attitudes, prejudices and stereotypes, instigating a gradual process of social change.

- Tries to actively involve everyone in the process. Through various interactive exercises the facilitator instigates interest in the subject, encourages the group to take initiative and makes sure everyone is included. All participants are important and have something to offer to the discussion, therefore they all need to be actively engaged. A facilitator needs to avoid having ‘favourites’ and needs to create an equal space for sharing. To do this, more ‘dominant’ members may need to be asked to ‘hold back for a moment’ and the ‘shyer’ members to be encouraged to ‘take the leap’ and join the discussion. Inclusion also necessitates that the diversity of the group is embraced, and that inclusive, non-heteronormative and non-heterosexist language is used.

- Translates what is happening in the group, not only by reflecting what has been said, but also interpreting it, so that the group can become aware of both the learning process and the group dynamic.

- Remains flexible and adaptable: at times, throughout the facilitative process, a facilitator may be put in a position where they need ‘to think on their feet’, think fast and come up with possible solutions as soon as possible. For instance, it is possible that when the workshop is about to start, things may not be as expected: there may be technical difficulties (with the projector, laptop, equipment); a considerably smaller or larger number of people show up; there are different degrees of ability in the group etc. Flexibility employs creativity and out-of-the-box thinking. Flexibility also means being able and willing to adapt the original plan to be more fitting to the group’s needs. Sometimes a group may need additional time to explore a certain concept because this is fundamental for their understanding and cannot productively move forward without it. At other times, the group may go through some concepts/activities much faster and without a lot of discussion because they may have explored the issue in the past and feel they have adequate knowledge about it. What is important is to be flexible and be able to make adjustments or changes, to the degree that these are possible.

- Helps the group overcome any difficulties it may encounter; resorts to conflict resolution; refocuses the group if it is diverting and helps the group move forward when it gets ‘stuck’.

- Manages time effectively and keeps processes within the required timeframes

- Strengthens, supports, empowers and positively pushes the group forward.

- Allows themselves to ‘fall gracefully’: issues related to diversity in relation to sexual orientation, gender identity and expression and sexual characteristics are not only personal and sensitive, but our understanding of them needs to constantly expand, keeping up with all new developments and new concepts. It is very possible that a facilitator may not be aware of a new term or concept or make an unintentional mistake. Falling gracefully means accepting being corrected, in a way that doesn’t silence them or push them out. But ultimately if they are leading with empathy, if they are willing to acknowledge when they mess up, and if they are willing to learn from those mistakes, that’s all that is needed.

● 5.2. Dealing with our own prejudices, anxiety, insecurity and stress as trainers

The importance of self-awareness and self-reflection[2]:

Before embarking on any training which includes sensitive topics such as gender, gender identity, sexual orientation, gender-based violence and sexual abuse, it is important that the facilitator is first aware of their own experience of the issues, their own sensitivities, belief system, values, attitudes and perceptions so they can be aware of how they bring these issues ‘to the table’ and into the training setting.

Through a process of self-reflection and self-awareness, the facilitator needs to be aware of how their own belief systems, attitudes, perceptions and own biases may be affecting the way they interact with the young people in the group. If a facilitator is for instance a passionate activist, a survivor of SGBV or are LGBTIQ+ themselves, could homophobic/transphobic/sexist attitudes or expressions of victim-blaming be triggering a certain reaction from them? Could they feel that their buttons are being pushed or are they having an instinctive motivation to ‘retaliate’ in order to ‘set the record straight’? Similarly, if a facilitator seems to inwardly agree with some stereotypical perceptions about the role of women or shares heteronormative/sexist/cisnormative beliefs, what kind of messages would they be giving to the group if their reactions are reproducing these stereotypes, albeit unintentionally? Could their responses possible cross the line and be discriminatory or could they possibly be creating a negative environment where not all people are feeling comfortable and included?

The challenge here is for the facilitator to maintain a balance of the personal and the public (Kerr & Huddleston, 2016), i.e. what they personally think and what they can express in front of others. The most important thing to remember, is that our job as facilitators is to create a safe and inclusive environment in the group, where all opinions can be explored in an unpolarised and balanced way. In order to do that, we need to leave our personal opinions aside and adopt an open and non-judgemental approach. Towards this end, the first step is to reach a very clear awareness of our taboos, stereotypes, biases and prejudices. Then it is important to recognize the negative impact these beliefs may have, if they are reproduced in a training setting, even though unessentially. The third and most important step involves a critical assessment on our part: to be able to adopt an open, neutral, accepting, fair, balanced and inclusive approach, we need to critically examine our own cultural assumptions that help us make sense of the world. In a way, we are called to challenge our own cultural and social understandings, perceptions and conceptualizations and question what we have so far understand to be our ‘truths’.

This entails a brave process of deconstruction and construction. Deconstructing perceptions that are stereotypical, discriminatory, normative, sexist, homophobic/transphobic/interphobic and striving to construct new conceptualizations, new ‘truths’ that are based on equality, respect for human rights, inclusion, acceptance of diversity and social justice. In this direction, it is important to consciously avoid the reproduction of negative attitudes against women, survivors of violence and people with diverse gender and sexual identities and to steer away from expressions, opinions, perceptions that perpetuate sexual and gender-based violence. Using inclusive language is vital (see section 5.5) as also consciously taking steps to foster an inclusive, safe and comfortable educational environment (see section 5.4). Even though the above may seem difficult to adhere to, framing our approach in the context of sexual rights provides a safe framework which enables us to leave our personal beliefs and possible biases aside.

Nonetheless, if we feel that adopting a different approach takes us way out of our comfort zone, is going against our fundamental beliefs (religious, cultural and otherwise) or we perceive that is severely threatening our integrity, it is important that we either refrain from conducting a training on sensitive topics, or we conduct the training with a co-facilitator. Our co-facilitator can then step in and respond to challenging questions or attitudes, which for us are uncomfortable.

Dealing with anxiety, stress and insecurity

Research suggests that at least 85% of people who need to make any sort of presentation experience anxiety. Fear of public speaking is normal and expected. It may be due to lack of confidence because we may think we don’t have adequate knowledge of the topic, or we do not trust ourselves that we are able to do a good job. Sometimes the awareness that we may be ‘the centre of attention’ may be quite stressful as we feel exposed. Nonetheless, we can deal with our anxiety and insecurities by:

- Preparing, preparing, preparing! Read up on your topic, brush up on your knowledge and definitions, especially on new ideas, concepts and issues related to the topic at hand. Make sure you understand the activity and the different steps of its implementation. But most importantly, be clear of what the objectives and the key messages are. What are you aiming at? What do you want young people to walk away with? With what knowledge, awareness and skills? What myths do they need to debunk and what stereotypes need to be challenged?

- Pick a topic that you love and is of personal interest to you. You will feel more comfortable presenting it

- Know your ‘audience’ well: who are they (demographics), what are their expectations of this training, how much knowledge do they have about the topic, what level of detail do you need to get into

- Prepare ahead of time for possible challenges: what parts of the activity/training could be challenging? What may be difficult for you or for the group? What if you have disclosure of abuse and people get emotional? What if there is conflict between participants? Sections 5.6, 5.7 and 5.8 provide various recommendations on how you can respond to these challenges. Similarly, the ‘Tips for facilitators’ section of each activity provides some information on what challenges you can expect and what you can do to address these challenges

- Good practice is synonymous with success! Practice in front of others and ask for their input. Work with a mentor or a peer trainer who can act as a ‘supervisor’ and provide constructive feedback: they can reflect what you’re doing well and help you work on what is challenging you. Use every experience as a learning experience and a stepping stone. The more you practice and the more exposure you have in training on certain topics, the easier it gets.

- Boost your confidence by updating your knowledge on the topic. You are standing in front of the group as someone who has at least a bit more knowledge than the participants on the topic. Really believing in what you ‘put out there’. Your group will feel if you really embrace what you say and will be more motivated to participate.

- Put things into perspective. Remember that 95% of your anxiety is not visible to others, even if you like you’re ready to have a heart attack! We also tend to judge ourselves harder than it is necessary. Most of the times we haven’t done as bad as we think we have.

● 5.3. Fostering participatory, learner-centred, experiential, non-formal education learning

Employing gender transformative learning with a human rights approach, entails stretching beyond the boundaries of knowledge and shifting attitudes, while at the same time building values and skills. Though knowledge of sexual and gender-based violence can be passed down through teaching, attitudes, skills and values such as acceptance, inclusion, respect, communication, empathy and critical thinking, need to be learned through experience. Towards this end, this toolkit, employs a variety of fun, experiential and interactive methodologies which aim to engage and motivate the learners. Some of the methodologies used include brainstorming, group discussion, buzz groups, role-playing, case-study analysis, debates, theatrical games and self-reflection, all of which enable young people to learn by ‘doing’, feeling and experiencing.

Learning takes place in a cooperative setting, where young people have the chance to learn from each other and to take ownership and control of the learning process. They develop confidence in sharing their opinions, engaging in constructive dialogue and exploring different perspectives on issues that directly concern them and have an impact on their own lives. By being engaged emotionally, learning is not only powerful, but it can be transformative as well. Experiential and participatory learning acts as a great instigator of transformation and change. Through a process of reflection and evaluation, young people are encouraged to challenge norms and think of alternatives, deconstruct stereotypes and limiting beliefs and construct new ideas, perceptions and attitudes based on equality, acceptance and respect of human rights. In this respect, this toolkit aims to empower young people to become ‘attitude shifters’ and ‘change bearers’, bringing about change in themselves and their sexual lives but bringing social change as well, by transforming the environment around them.

It is important that facilitators provide an open, enabling and supportive environment, which allows the space for young people to engage in this process of deconstruction and construction, which ultimately entails an attitude shift. By challenging norms, creating awareness on discriminatory, unhealthy , coercive or abusive behaviours and empowering young people to stand up to sexual and gender-based violence, young people can fully enjoy their rights and build a happy, positive, healthy and safe approach to their sexuality.

How to apply experiential learning in practice

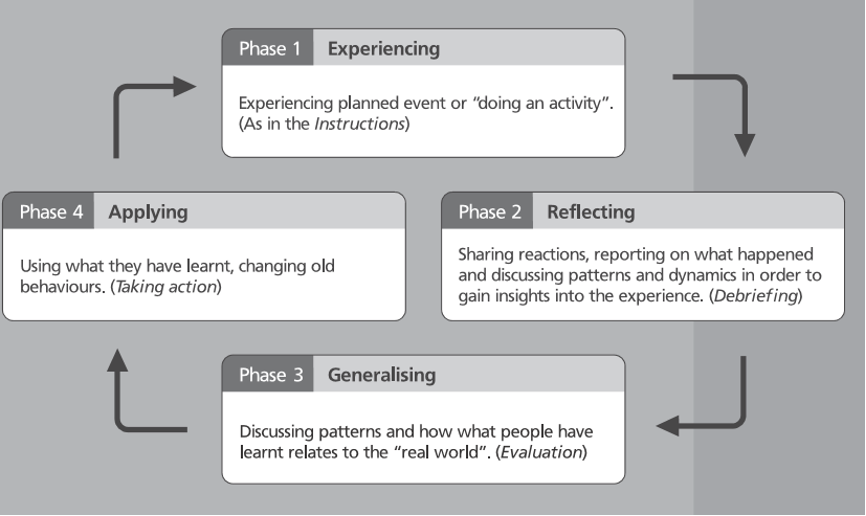

David Kolb’s cycle of experiential learning (1984) best describes how we can apply experiential learning in practice. The learning starts with exposing participants through a structured experience such as a role play, debate, theatrical game, a case study etc. (Stage 1: Experiencing). Once the activity has been completed, we go into the debriefing stage (Stage 2), where invite participants to observe what they experienced and reflect on it. On one hand, the participants reflect on everything that has happened during the experience and, on the other hand, through a process of introspection, they explore the emotions and thoughts associated to the experience, exploring patterns and dynamics so they can gain an insight into the experience. Following the sharing of thoughts and emotions, the discussion zooms-out to what happens in real life through a process of generalization (Stage 3). The aim is to build a bridge between the personal experience and ‘the real world’, helping participants to connect the dots of a new mind map/conceptualization of something in the world around us. We then move to stage 4, Applying, where participants are encouraged to test or implement their newly acquired competences and to change old behaviours. In this way, experiential learning provides the space for rehearsing personal or social change.

● 5.4. Creating a safe, comfortable and inclusive space for the workshops

Fostering an inclusive, safe and comfortable educational environment means that the diversity of genders and sexual orientations are not only welcome in the educational process but also visible, accepted and respected. It also means ensuring that the needs, opinions and diversity of all participants are taken into consideration.

Including pronouns is a first step toward respecting diverse gender identities, working against cisnormativity, and creating a more welcoming space for people of all genders. On the contrary, assuming a person’s gender identity based on gender expression (as shown through their mannerisms, clothing, hairstyle, appearance etc.), can be exclusive, discriminatory and even derogatory for some people, as not everyone matches their gender identity with their appearance.

Go around the room and ask people to share their name and their pronoun (for instance ‘ I am Caren and I identify as a ‘she’, I am Martinez and I identify as ‘they’ and ‘them’ etc.). Include pronouns on nametags and during introductions. Make sure you refer to the correct pronouns when giving instructions for an activity, during debriefing and during group discussions. Encourage participants to also use the correct pronouns. If you accidentally make a mistake, don’t make a big deal out of it. Apologize and quickly use the correct pronoun. Providing space and opportunity for people to share their pronouns does not necessarily mean that everyone feels comfortable or needs to share their pronouns. Some people may choose not to share their pronouns for a variety of reasons and that is okay. In such cases, refer to this person only by name.

Remember that all diverse identities need to feel adequately represented and ‘present’ in the educational process, be it in the actual activities themselves, in language, discourse, communication and social interactions. Use non-heteronormative, non-cisgender language (more on this in section, 5.5).

Remember that you don’t know anyone’s sexual orientation or gender identity unless they tell you. Don’t assume that everyone is cis-gender and heterosexual and be inclusive of all gender identities, sexual orientations and the diverse shapes of families when using examples or case-studies. Also be mindful of derogatory, discriminatory words that may make feel people offended, even if they’re used in ignorance (such as hermaphrodite, transvestite, faggot etc.). When talking about gender and sexual orientation, try to use correct terminology; examples of these definition are outlined in the theoretical section of each module and you can use them as a reference. Moreover, confront comments that are heterosexist or gender identity biased when you hear them. Respond when you hear others using non-inclusive language, making derogatory jokes, using incorrect assumptions/stereotypes, voicing misinformation, etc. Explain, in a generalized way and without targeting the person who made such comments, how such comments may be inappropriate or offensive and explore alternative terminologies, definitions, comments. And most importantly, as Killermann &Bolger (2016) mention, respond to challenging comments with ‘courageous compassion’, compassion that is rooted in empathy, even for the most ‘difficult’ participants. This would mean genuinely trying to understand, with authentic curiosity, an opinion that may be diametrically opposed to ours and exploring it as an alternative perspective.

Invite all young people to engage in the learning process and ensure that they all actively participate in the activities by paying specific attention to include the ‘voices least heard’, so that people from the more marginalized groups also have a voice in the training experience. This ensures that the perspective of people with all diverse identities is shared and listened to.

Create a safe environment by setting the tone and acting as a role model. Exhibit openness, acceptance and respect of all the diverse expressions of gender identity and sexual orientation yourself. Adopt an accepting and non-judgmental approach to people’s different experiences of sexuality. This stance will inspire participants to do the same. By fostering an environment where participants feel safe to participate in the discussions, you help to dispel misinformation, confusion, and stereotypes, which leads to a better understanding of the diversity of people around us. This enhances tolerance and acceptance, which in turn supports a learning environment that is free of negativity, aggression, discrimination, abuse and oppression.

A secure space for vulnerabilities

Moreover, when we walk into a training session, it is also important to keep in mind that do not know the life experiences of our participants, their specific contexts, specific situations that may put them at risk and/or experiences of abuse. Thus it is of vital importance to create a safe space for them to feel comfortable to engage in the learning process.

Participants may feel vulnerable when they ‘put themselves out there’, when they take the risk to share something intimate/personal/challenging/different/controversial, in trust that this risk won’t result in their undoing. In the same way, vulnerability may take the form of participants engaging in an activity, discussion or process, without being exactly sure where this is heading and completely trusting the facilitator to be their guide. One of our most important tasks as facilitators is to create an environment of trust, comfort and confidentiality within the group right from the beginning. This can be achieved through icebreakers and teambuilding, setting ground rules, maintaining a positive climate in the group, responding to and dealing with negative emotions or behaviours and actively encouraging participants to express their opinions without being judged, criticized, attacked or stigmatized.

Allow discussions to take place only in the context of mutual respect and promptly respond to expressions of negativity that are disruptive to the group. Never allow a person to become the ‘target’ of the group and it is your responsibility to protect them. Moreover, respond with empathy, kindness, understanding and patience, especially for people in the group who may be impatient, challenging or create obstacles. Encourage each person to share in the group only to the extent that they feel comfortable to do so. They may even decide to exercise their right to ‘pass’ (i.e. not answer) on a question, if they feel the need to.

Don’t directly ask participants to share personal stories or experiences (unless they themselves consciously decide to do so) and try to use examples in a general context. If there is disclosure on a sensitive subject, handle it with sensitivity and discretion. Try to put it in a generalized context so that the focus is no longer on the person who shared the story in an effort to protect them from any stigmatization. You can then follow up with the person one on one if you feel there is a need to do so.

Guiding principles for creating a safe space for vulnerabilities

- Safety: The space is one in which participants are physically and emotionally safe and can be themselves without fear. Ways of creating this include inclusive language, group agreements or group ‘rules’ to abide by during the learning process, and having clear exits from the situation should participants relate too closely with a topic and may require the space to process or additional referrals for support.

- Transparency: The facilitators need to be clear and honest in their interactions with participants. This includes letting participants know what to expect in upcoming sessions and admitting when you don’t know something. Additionally, ‘content warnings’ could prove useful prior to showing certain audio-visual material or prior to working with certain stories where extreme manifestations of SGBV are presented (physical attacks, murders, rape etc) so as participants can be prepared beforehand and pace themselves if they need to.

- Peer collaboration, interaction and support: Provide opportunities for participants to interact with, collaborate with, support and learn from each other. This gives participants power within the sessions and gives them chances to form positive, healing connections. Question and answer sessions, working in small groups/pairs, discussions, roleplays, theatrical improvisations and games are all examples of this.

- Empowerment: You want to build a space that gives participants power and choice in the interactions. A key way to do this, is by treating youth as experts on their own experiences. This includes ‘sharing the power’ with them and making them ‘owners’ of their learning process. By using non-formal education methodologies, avoid lecturing or the dry provision of information: instead, opt for creating a dialogue, inviting young people to provide their own suggestions, come up with possible solutions and guide the discussion on topics that are most relevant to them or that directly affect their own realities.

- Awareness of population specific issues: Certain racial, ethnic, sexual, and gender identities may be more or less likely to face certain forms of violence, discrimination, or health issues. Ensure that the experiences of all groups are visible in your training sessions.

● 5.5. Using inclusive language and why it is important

Cis-normativity, heteronormativity and heterosexism[3] is often the origin of violence against people with diverse gender identities and sexual orientations. The social regulation of gender, which frames gender norms and also the interactions between people, places anyone who diverts from the norms at risk for victimization. By normalizing and privileging heterosexuality, cisgenderism and heteronormativity through language and daily routines, we explicitly or implicitly communicate messages about what is acceptable about a person’s gender and sexual identity, therefore marginalizing people of certain identities.

The use of words and characterizations of LGBTIQ+ people poses various challenges and often becomes an issue. Many words that are used to describe LGBTIQ+ people often carry a negative connotation or are used in a derogatory way to exercise bullying or intimidation, so great care is needed with regard to how these words are used. Younger people (especially teenagers) may often use such derogatory words as a ‘joke’ or just “throw them out” in order to make fun or to offend someone, also reproducing stereotypes, prejudices and stigmatization. Respond to this by explaining how such words are derogatory and that such expressions are unacceptable because they hurt people. You can also make a reference to the group agreement about inclusion, respect and consideration of another person’s emotions: any person in the learning environment is allowed to express their identity as they experience it, without being criticized, ridiculed, gossiped, marginalized or harassed for it.

Using gender-neutral and inclusive language is one of the simplest, most proactive ways that as facilitators we can create a safe and inclusive environment of all LGBTIQ+ identities. Not only does it make people of diverse identities feel included, but it also helps participants develop more respectful and inclusive vocabularies. Being inclusive in our words, entails avoiding terms and expressions that may reinforce inappropriate or outdated attitudes or assumptions about gender and sexual identities, such as

- Reinforcing the gender binary by assuming or implying that there are only two genders that exist and are valid.

- Reinforcing heterosexism by assuming that everyone is heterosexual

- Using outdated and potentially offensive terms to describe gender or sexual orientations

The following are examples of better go-to language, though sometimes the terms replaced might still be appropriate in certain situations or contexts. Use your judgement according to what would be more suitable.

- Avoid the gender binary by using expressions such as they, instead of he or she; people, instead of women and men; students/young people, instead of boys and girls; siblings, instead of brothers or sisters; parent/guardian, instead of mother/father; partner, instead of boyfriend/girlfriend.

- Avoid some outdated terms, which might be offensive because they could imply pathologizing or they could simply reflect inaccuracies. For instance:

- Instead of “transsexual, or transgender” use “trans”

- Instead of “transvestite,” use “cross dresser.”

- Instead of “sex change” or “sex reassignment,” please use “gender affirmation” or “transition care”

- Instead of “preferred gender pronouns,” use “personal pronouns.”

- Instead of “hermaphrodite,” use “intersex.”

- Instead of “homosexual,” use “gay” or “lesbian.”

- Instead of “lifestyle” or “preference,” use “orientation” or “identity.”

● 5.6. Teaching about sensitive and controversial issues in a non-formal educational setting[4]

Talking about gender and sexual diversity, power hierarchies, sexuality and SGBV itself may often lead to an atmosphere charged with strong, and sometimes negative, emotions, as discussions may generate conflicting opinions, stances and beliefs. On one hand, this expression of emotions is actually beneficial for participants, as this has a positive effect on their learning and the overall educational process of the whole group (Dankmeijer, P, 2011); on the other hand, however, it puts the facilitator in a challenging position as they need to respond effectively to this emotionally (and often intensely) charged environment.

The challenges a facilitator may face in such a situation include (Kerr & Huddleson, 2016):

- Maintaining a balanced attitude, remaining objective and not being drawn into the discussion.

- Responding to and safeguarding participants’ sensitivities: extreme views and negative attitudes may lead to other participants feeling under attack, offended, harassed or marginalized.

- Containing the heated-up climate in the group and preventing it from overheating so that it doesn’t climax into a conflict.

- Having adequate all-encompassing knowledge on the topic to be able to address it from the sociological, political, historical, cultural, religious and psychological perspective.

To respond to the above challenges in a training setting, the facilitator needs to first understand why participants have these strong emotions and where their views and stances are coming from. For instance, it is very possible that emotional reactions are triggered because of ignorance, misinformation, myths and stereotypes, normalized beliefs about violence, a recent upheaval in the media, religious beliefs and by enlarge how realistic or not these beliefs are.

Secondly, an important parameter on how a facilitator reacts to negative emotions and stances is the way they interpret the participants’ reactions and strong emotions. A facilitator may react differently if they interpret these reactions as blatantly phobic (homophobic, transphobic, interphobic) or discriminatory or derogatory and therefore would rush into a defensive mode to “set the record straight” while, on the contrary, they will have a very different reaction if they consider that this negativity expresses a process, during which participants are working through their ‘obstructive’ convictions and could potentially reach an attitude shift.

Reframing negativity in the context of “obstructing convictions” allows facilitators to view negative inclined participants not as the “enemy” (and hence limiting their empathy and connection with them) but instead as persons engaged in a process of working through their unconstructive ideas, who are rethinking their inherited beliefs, and are deconstructing old concepts that are causing discrimination and marginalization. Allowing and creating a space where participants can self-reflect, re-evaluate and challenge existing notions and stances, allows for a process of deconstruction of normalized, stereotypical, negative, even phobic beliefs and the construction of new understandings and stances, based on mutual respect, real inclusion and equality. (Dankmeijer, P., 2017).

Responding to negative emotions

Maintaining objectivity and impartiality

Adopting a balanced approach, requires for an open discussion to be instigated so that a wide range of alternative views are expressed, with the facilitator refraining from revealing their own views and remaining objective. Even though it is challenging, it is necessary that the facilitator remains as ‘impartial’ as possible and to avoid being drawn into the discussion or engaging in one-on-one dialogue with participants. What is important is to provide fruitful ground for participants to explore, rethink, challenge and re-evaluate various stances and opinions, and particularly the negative ones. Remaining objective and balanced does not mean that the facilitator will give equal weight to negative opinions or emotions though: on the contrary, the discussion will open up so that arguments and counter-arguments can be expressed, to explore a topic from different angles.

In the event that participants find it difficult to present counter arguments, then the facilitator can play ‘devil’s advocate’ to help instigate this reaction. Additionally, open ended questions can be creatively used to challenge negative stances but in a generalized context rather than at a personal level (for instance responding with something like ‘One could also say that……’, or ‘The counter argument to this is….’ Or’ Some people believe that….’). We do not want to put people on the spot. Even though participants with negative emotions may seem to be ‘disturbing’ the group, they are also part of the group and they need to be treated with respect without being stigmatized or marginalized. When we can creatively use what they bring on to the table, this can be an opportunity for leaning and growth of all participants.

Lastly, even though impartiality is recommended so that the facilitator does not provide their personal opinions, there are times when they may find it useful for the group’s process to disclose some personal information about a similar experience. Sharing can add to the evidence on a topic, can aid understanding and can help participants deepen their perspective. So, for example, disclosing a personal experience on cyber-bullying (which may or may not be related to an intimate relationship or to SOGIESC diversity) may help the group better understand the impact and effects, without going into precise private details of the nature of the bullying (Kerr &Huddleston, 2016).)

Asking for clarifications

While it is important for all participants in the group to feel respected and included in a training environment that generates openness, trust, honesty and non-judgement, it is recommended that the facilitator does not take on board just any expressed opinion. To help participants better explore and question the negative opinions expressed, the facilitator can first ask open ended questions for clarifications, i.e. ‘What do you mean when you say that…’, ‘Can you explain what…means for you?’. (Dankmeijer, P. 2011). This grounds the discussion and gives a chance for the person to rethink what they have said and also provides room for the group to further explore misconceptions, prejudgments or stereotypes.

Reflection and paraphrasing

Sometimes a participant may not understand how negative their opinions are. By ‘feeding’ them back to them through reflection and paraphrasing (i.e. summarizing what they have said in our own words) and checking with them that we understood right (‘So if I understand correctly, what you have said is……Is that correct? Did I understand right?), the participant has a chance to hear their own words, pause, rethink and have the opportunity to explain or explore them further. Our intention when we reflect and paraphrase is to try to act like a mirror to the persons and not act like a parrot. Reflecting and paraphrasing doesn’t mean we repeat word for word what we heard: it means we try to restate the fact and reflect on the feelings or intentions that may emerge from participants’ statements.

Even though it is important to allow the person who has expressed negative opinions to reflect on them, it is important to avoid engaging in a one-on-one discussion with this person. The aim is not to try to change this particular individual but instead to provide food for thought for the entire group to explore where they stand and work through their own prejudices or judgements. A good technique to follow reflection and paraphrasing is to draw upon the opinions of the whole group, by opening the discussion to all. Again, we need to be aware of not allowing the discussion to become polarized (as this may escalate to conflict) but we keep the dialogue grounded by reflecting and summarizing the different opinions heard.

Responding to negativity arising from religious views and beliefs

Religious beliefs are often well engrained in an individual’s values system. It is widely believed that there is convergence amongst most religions in the fact that they condemn homosexuality and male homosexual behaviour in particular.

It is recommended that a facilitator approaches the topic of sexual orientation and religion by discussing religious beliefs as separate from religious texts and to point out that religious beliefs are formed in a multidisciplinary context, which involves an interplay of historical, social, cultural and spiritual aspects. Making a distinction between the actual religious texts and spirituality, often helps provide some common ground for further exploring tolerance and acceptance.

Discussion of the religious texts as such is unnecessary and could be harmful. The most effective way to discuss religion-based convictions about LGBTIQ+ issues is to frame them in the wider human rights context. In the frame of equality, respect, freedom of expression, the right to make our own choices and the right to be protected from harassment and discrimination, the facilitator brings forth a series of dilemmas which arise due a perceived ‘incompatibility’ of these rights with religion (Dankmeijer, P. (2011). The aim is to guide participants to engage in a more critical discussion, to explore these incompatibilities, to develop empathy towards LGBTIQ+ persons and to enhance understanding of the impact negative attitudes have on them. By engaging in a discussion on sexual orientation and religion, we are not asking of people to change their religious identity or to become less religious; instead, we are asking them to re-evaluate beliefs and stances and cultivate behaviours that promote equality, inclusion and acceptance.

Responding to negative emotions that are offensive, verbally aggressive and hurtful

Even though the participants are aware of the group ground rules and the context of respectful disagreements, it may be the case that some people may become too emotionally charged and end up being verbally aggressive, using derogatory and hurtful words to talk about LGBTIQ+ people or about certain groups which experience SGBV (Roma, sex workers, women) . In the unlikely event that a participant becomes offensive, it is important to respond right away and to firmly set the boundaries. While we acknowledge that discussions on gender and sexual diversity may stir strong emotions and strong reactions in individuals, it needs to be made crystal clear that offensive, derogatory and abusive behaviour is unacceptable. We need to help the individual reflect that what they are saying has ‘crossed the line’ and that other people in the group may feel offended or that the overall safety in the group is threatened.

Remind the group of the ground rules and try to de-escalate the situation by re-focusing the group on the issue at hand. Diffuse the escalation by keeping the discussion unpolarized, concentrate on the impact heteronormative opinions and stances have on LGBTIQ+ people and guide the group to explore a common ground on which they can all work to bring about change.

What if this escalates into a conflict? How to manage conflicts.

If a group is expressing very strong emotions which continue to escalate and the environment is becoming charged, it is probable that conflict may arise. Sometimes conflict is unavoidable because of the different perspectives, experiences, socio-cultural background, religious beliefs, values and the different expressions of sexual diversity within the group. Even though we tend to fear conflict for its possibility to be destructive, we also need to recognize that it can be equally constructive, if handled and channelled in the right direction.

Conflict becomes destructive when arguments are one-sided; the safety of group members is threatened; there is directionless anger, emotion and tone; there is aggression exhibited through body language and/or bullying; and the positive group dynamic seems to be shaken up. Alternatively, conflict is constructive when it is used as an opportunity for participants to explore various perspectives; discuss new ideas and new concepts; start focusing on common goals (i.e. explore what is the common ground between them, what they all agree with and what they identify as the common problem); and explore how to bring positive change to this problematic situation. If used constructively, conflict can help enhance the group’s cohesion and bonding and can contribute to individual and group growth.

A good effective approach to conflict is to first anticipate it. When we are preparing for an activity it is important to question which parts of our activity are the most controversial, what sensitivities they may touch in our group and which parts/terminologies/issues are likely to evoke strong reactions. Acknowledging the possibility of conflicts arising and anticipating them, frees facilitators from taking conflicts personally and/or thinking that perhaps they are a result of something that they have done. Conflicts are not the facilitators’ fault. They are sometimes an inevitable part of the process.

To contain the conflict and diffuse it, first we need to acknowledge what is happening and reflect on the fact that the issue is stirring very strong emotions in participants. We also mention that even though it is beneficial for each person to acknowledge and express their emotions, it is very risky to allow ourselves to be carried away by them. Thus, we invite participants to engage in a more fruitful discussion, explain their thoughts speaking only for themselves and using I-statements. We also remind them to be careful with their language not to offend each other and to refer to the ground rules of listening without judgment, mutual respect, no interruptions when the other party is speaking and everybody taking full responsibility of their own words and actions.

Some specific mediation skills may come in handy. First define the conflict (and the social context of the conflict) ➔ then acknowledge the strong feelings that emerged ➔ guide participants to generate a common vision of what they want to ultimately achieve (i.e. what is the commonly identified problem) ➔ and finally arrive at an agreement of the way to solve the problem.

Remember that to resolve the conflict, it is important to guide the participants to explore a win-win situation, i.e. a common stake that they all share. Usually this common stake lies in the framework of human rights, as no person would ever agree to a human rights violation. In this direction, we encourage participants to seek for solutions towards a commonly identified problematic situation (i.e. young people being bullied, harassed, abused etc.), by safeguarding their human rights (equality, respect, freedom of expression, the right to be protected from harassment and discrimination).

● 5.7. Dealing with difficult questions

Questions about sexuality and violence sometimes tend to put us in an uncomfortable position because they touch upon sensitive issues , most of which are hardly talked about because they are taboo. It is also possible that our discomfort may arise from the fact that some questions make ‘shake up’ our own belief system and values or they touch very personal issues in us too. However, it is important to remember that when young people, and especially teenagers, are asking questions about sexuality, this reflects that:

- We have already created an environment of safety and trust, which means that young people feel comfortable to ask questions

- They are in a process of questioning and developing critical thinking and want to explore alternative perspectives

- They are trying to figure out where they stand, and they’re perhaps reflecting and evaluating their own prejudices, misconceptions and stereotypes

- They could be responding to an injustice or an unhealthy situation and are exploring how to take a stand against human rights violations.

- They are developing assertive behaviour, which reflects self-esteem and confidence, as well as empowerment

Tips in answering questions about sexuality and sexual and gender-based violence

Remember that we need to answer:

- Always! Do not ignore a question, even if it makes you feel uncomfortable. Not responding to a question gives the message that some things are better not talked about and reinforce stereotypes and taboo

- Honestly, succinctly and clearly: hesitating to answer or reflecting discomfort about a question could instil feelings of shame or embarrassment to young people

- Being aware of your non-verbal communication because it may communicate distaste or disagreement.

- With respect, non-judgement, openness and sensitivity. Also by maintaining confidentiality and trying to protect young people from becoming stigmatized. Putting things in a general, non-personal context is always helpful.

- As naturally as possible and without shame (even though you may feel you are getting out of your comfort zone)

- Providing relevant information ONLY in relation to the question (do not side-track and be to the point)

- Using all-inclusive language and language that does not cultivate heteronormative, cisnormative and sexist beliefs.

- Including many points of view in your answer in an effort to cultivate critical thinking

- Trusting your instinct and intuition. Maybe you’re feeling that there is something underlying the question and needs to be addressed.

- Trusting yourself and having the confidence in yourself that you can handle the question. The mere fact that you’re facilitating this workshop means you have at least some extra knowledge that the participants don’t.

- Using the question as a ‘pedagogical’ moment (i.e. a pedagogical opportunity) to reinforce positive attitudes, stances and beliefs

- If the question is too challenging, buy some time to have a think about it. Pause and say, ‘Lots of people ask this question’ or ‘Thanks for asking that because this gives me the opportunity to….’. Also check for the person’s understanding: ‘Does that answer your question?’. This gives you the opportunity to rethink and revisit the question. In general, for challenging questions, you can use the ‘stop, drop and roll’ technique: stop to have a think, drop your personal beliefs, roll the question into a discussion topic in the group. For instance, you can say “Has anyone else been thinking about this? What other people think about this?” or ‘Thanks for the question. I’d like to hear what other people are thinking about this…”

- By remembering that even the mere fact that you are willing to listen to a young person with openness and non-judgement, makes them feel valued and that their voice or their concerns are valid and heard.

The 5 types of questions and how to respond to them[5]

Usually questions are related to the following 5 types:

- Information seeking

- Is it normal? Questions

- Personal beliefs

- Personal questions (to the facilitator)

- Provocative questions or questions that aim to shock

Information seeking

In general, these questions are the ‘easiest’ and more ‘manageable’ because they are factual. Answer in an age-appropriate manner, without giving complicated answers, avoiding to sound ‘too scientific’ and steer clear from technical jargon. The aim is to help young people challenge norms, not to prove your academic knowledge or to show off. If the question contains a values component or is touching upon belief systems, make sure that you open up the discussion and various points of view are presented. Remember that even though you’re responding to the ‘facts’ it is also important to briefly include social and cultural aspects, with the aim to cultivate positive stances and healthy, respectful, accepting attitudes. For instance, if a young person asks about intersex people, it is also important that, together with the definition, you also explain that intersex people are a group who are marginalized because their diversity in sex characteristics challenges our core perceptions of biological sex. Similarly when asking what free, active and meaningful consent is, together with the definition also explain that in some cases and contexts young people may pledge their sexual agency to their partners and foster compliance, which is the opposite of consent. Lastly, don’t feel embarrassed if you don’t know the answer. Be honest and say that you don’t know, promise to look it up and hold true to your promise and say the answer next time you meet the group.

“Is it normal?” questions

When we open up the space to discuss attitudes, stances and behaviours that have to do with gender, sexuality and relationships, it is natural that young people will try to explore what is ‘normal’ and what is not. This is actually very useful because on one hand it opens the space to discuss diversity and identities/behaviours that do not fall into the ‘norm’, while on the other hand, it allows facilitators to challenge unhealthy behaviours or negative attitudes which are often ‘normalized’. When such questions are asked, start by validating young people’s concerns in a general context “Many young people think that…” or “It is common belief” and then offer the alternative. For instance, if you’re discussing if it is okay for someone to share an intimate picture of their partner with others as long as they do it as a joke and don’t mean any harm, you can respond with something like this ‘Many young people think that it is okay to share a nude pic as long as you don’t mean any harm. However, is this act consensual? Has the other person agreed to it? Does this behaviour violate any rights of the other person? How about the right to privacy and protection from abuse?’. You can also refer young people to other resources as appropriate so they can find more information.

Questions that touch upon personal values and belief systems

When questions that touch upon personal beliefs are asked, don’t try to persuade the young people about what is right or wrong. Instead, try to guide them to find that answer for themselves. Open up the discussion and present all different views without being biased towards specific opinions. The ‘journalist technique’ could also prove useful in this case; it is important to present both sides. For instance, you may have resistance to presenting the church’s views on homosexuality but it is important to do so as one aspect of the story. The other aspect is the one that is supported by human rights, which calls for freedom of expression, acceptance of diversity and protection from discrimination and abuse. After young people had a chance to hear all the different aspects of the topic, follow up with questions that instigate critical thinking. Provide food for thought and challenge opinions and attitudes that are negative, disrespectful or discriminatory. It is also important that when questions of values arise, that you are aware of your own beliefs and keep them out of the process. Try to maintain a neutral attitude without sharing your own values. Use the technique of depersonalization and generalization: Instead of asking “Why do you believe this?”, you can say: “Why do you think some people believe this?” This avoids putting young people in the defensive.

Personal questions

Answering a personal question depends on the question itself, your degree of comfort in answering the question, the broader relationship you have built with the group of young people, and the degree of intimacy that exists between you. Also remember that as facilitators, we also have the right to privacy and to the protection of our personal data, just like any other person. So don’t feel obliged to offer personal information if you don’t want to, don’t see the point to it or you believe that it would make you feel exposed. Revealing something personal about ourselves, we can’t take it back. You can always present your point of view by putting it in a general context: “Some people believe this………….” You can also use humour and divert the question to something that can be answered in a generalized context.

Sometimes, depending on the question, it may feel okay to answer. You may decide to share a personal experience to build group cohesion or demonstrate empathy – however never to meet your own needs or to win favour with young people. In any case, avoid sharing information about personal sexual practices or behaviours.

Questions that are provocative or aim to shock

Usually these questions sound as if they are unsubstantiated and meaningless, and are intended to shock, to provoke a reaction or to entertain others. While it may feel that your buttons are being pushed, it is important to keep your cool and respond calmly and soberly, giving a serious, rational answer. Remaining cool and professional gives the message that you take things seriously and helps ground any tension that may have arisen because of the provocative question. Moreover, be sure you reframe the question, in something that is relative and useful, using the correct terminology and respectful language. This helps give out a message of what is appropriate to say and what is not. It is also good to remember that questions of this nature can hide real concerns or questions that young people are ashamed to ask otherwise. Whatever the case, they always deserve an honest answer.

The box of anonymous questions

As young people may feel shy or hesitant to ask questions about sensitive issues in front of others, it is important to find a way to provide the space where questions can be asked anonymously. A good option is to use the ‘box of anonymous questions’. Once you complete the debriefing and wrap up of an activity and you still have time left, you can invite young people to ask any questions they have anonymously, by writing them on a piece of paper and putting them in a box. You can then pick out a question at random from the box and discuss it the group.

Before doing so, set some ground rules with the group: you will not read out any questions that are offensive or use derogatory words, you will skip questions that are not relevant to the topics discussed today and you will skip questions that ask about issues that have already been discussed. This gives you some control over what can be discussed so it is framed in a relevant and respectful way.

Examples of sensitive questions and how to respond to them

✓ Since heterosexuals don’t discuss their sexuality, why do gay/bisexual people need to discuss theirs?

Heterosexuals express their sexual orientation when they mention (or introduce) their boyfriend, girlfriend, husband or wife to another person; when they place a family picture on their desk at work; when they give their significant other a kiss goodbye at the airport; when they talk about a celebrity whom they find attractive; when they are celebrating a wedding anniversary; and when they hold hands on the street. They have no need to let people know in a specific way what their sexual orientation is, because their actions and words over time let everyone know they’re heterosexual. People of different sexual orientations who do precisely the same things, however, are often accused of “flaunting their sexuality” or of “throwing their private lives in other people’s faces.” They may be scorned, harassed or attacked. Being forced to keep one’s sexual orientation a secret can be difficult and exhausting and it also constitutes a violation of human rights.

✓ Wouldn’t all these things that we are discussing about sex positivity make us lose our values and lead to debauchery and immorality?

The link between sex and morality is a very common one. Why do you think this is so?…… What does society teach us about the morality of sexuality?….. And why do you think we are now discussing alternative discourses about sexuality?…..How do these alternative discourses relate to human rights?…. Once the group has expressed their answers, you can wrap up with:

On one hand we have what we have learnt about the moral and the right way to express our sexuality. This has become our ‘norm’ and what we have been conditioned to believe is the right way to have ‘acceptable’ sexualities. At the same time, we also need to acknowledge that sexuality is linked to the fulfilment of human rights, namely the right to freely express one’s sexuality without discrimination, domination, inequality or abuse. Freely expressing one’s sexuality is ultimately a quest for happiness and the need to reach the maximum level of well-being; it is also based on the universal aspects of respect (for oneself and for others) and equality, both of which are moral qualities.

Expressing one’s sexuality in the way a person feels it is right for them, does not mean that the person has disregarded their value system. It is possible to have a free, informed and positive sexuality, while at the same time maintaining your value system especially values that connote respect, understanding, consideration, love, equality and safety. What we are often asked to question is not whether people who express their sexuality openly and freely are debauched; but to understand the extent that imposed perceptions about morality are allowing (or not) young people to fulfil their rights and ultimately reach the ultimate and most desirable level of well-being for themselves. For instance, how are perceptions about chastity and virginity making women more vulnerable to abuse because they are not able to own their own bodies and their own sexualities? Or how are perceptions against same-sex relationships dooming young people to exclusion, marginalization, depression and many forms of abuse? Only when young people can express their sexualities freely, in the way they experience them and want to express them can they be truly happy and fulfilled.

✓ Is it normal for your partner to ask you to watch online pornography before you have sex? Isn’t that perverted and a form of violence if you don’t want to use them?

All couples (whether they are of different sex or the same sex) can have sex and give pleasure to each other through various sexual practices. How each couple has sex and finds pleasure is very unique and very personal for that couple. As long as there is free, meaningful, informed and mutual consent, then there is nothing ‘perverted’ in the way a couple decides to find sexual pleasure. No partner however should feel pressured, coerced, intimidated or pushed to engage in any sexual practices that they don’t feel comfortable with or for any reason don’t want to engage in. If this happens, then yes, it is a form of sexual abuse and it needs to stop. You can have an open discussion with the partner about how you feel and if the behaviourcontinues it is important to reach out to others for support.

✓ When does kinky sex become abusive?

Kink suggests any sexual activities that fall outside the spectrum of what society traditionally considers as the ‘norm’, ‘acceptable’ or ‘mainstream’ about sex . There are many different types of kink in a relationship, including fetishes, role playing, exhibitionism, polyamory, clothing fetish, leather, voyeurism, bondage, dominance, submission and sadomasochism (BDSM). All kink is comprised of a power dynamic between partners enacted through various activities. Because kink relationships are based on a power exchange between partners, it can sometimes get fuzzy whether boundaries are crossed and this exchange has become abusive.

The most important aspect in a kink relationship is consent. Partners need to negotiate and agree to all sexual practices, roles and boundaries beforehand without pressure, coercion, intimidation or threats. There needs to be a clear understanding of what the kink relationship will entail, and a true, active, and mutual agreement needs to be reached that both partners are okay with this. There also need to be clear boundaries as to what each person considers desirable and acceptable and both partners maintain the right to ask for a certain behaviour to stop if they consider it undesirable or if it is no longer pleasurable for them. Consent can also be withdrawn at any time, for whatever reason.

Sometimes, though, abusive behaviours may be masked in the name of “domination.” The first sign of an abusive behaviour in kink is a behaviour that constantly crosses and disrespects the negotiated boundaries. Especially if a partner is feeling that their ‘boundaries are pushed’ and ‘limits are explored’ (as is the common objective in kink) beyond what they would be interested in and beyond what is acceptable, desirable or enjoyable for them. Moreover, words like “I know what’s best for you” in a context that’s not part of the negotiated boundaries can be a sign of abuse. Towards this end, ignoring a partner’s safe-word and continuing with an undesirable kink practice is the most prominent red flag for abuse. Lastly, as community is often an important aspect for people who practice kink, attempts to remove and isolate a partner from the said community (with excuses that ‘I no longer want to share you with others’ or ‘why can’t we just be enough for each other’) are also signs of abuse; attempts for isolation could be aiming at having the ability to more easily have control over the partner.

✓ Why do I have to call someone by a name that is different than their legal or given name? Isn’t their given name the correct one? Why such fuss?

Despite heteronormative perceptions that are strongly instilled by society, it is important that we try to expand our awareness of gender and view it as a spectrum rather than a binary division between males and females. While some people do identify as women or men, some people may not identify themselves within the gender binary. Gender constitutes an important part of someone’s identity and it is very important to respect each person’s self-identification. People have a right to self-determine and express their gender in the way they themselves experience it and not according to what society says is “right”. Therefore people may opt to use a different name than the one given to them legally at birth, so it better reflects the way they experience their gender. Unfortunately, various societal taboos have prevented societies from allowing legal recognition of various gender identities and in some countries people outside the gender binary may not be able to legally change their name. Despite the legal situation, at a personal level we can all show respect of other people’s expression of identity. It is their human right and it is important that it is respected. Continuing to use a name or a pronoun that does not correspond to what a person wants to use for themselves, violates other people’s rights, perpetuates intolerance of diverse gender identities and sustains transphobic beliefs and attitudes.

● 5.8. How to respond to disclosure of violence and abuse[6]

An important thing to have in mind when you walk into a training setting is that you never know ‘who is in the room’. Young people may be exposed to different forms of SGBV at different stages of their lives. They may have experienced gender-based bullying at school or sexual harassment, they may be living in a household that is affected by domestic violence or they may experience abuse in their own relationship with their partner. While facilitators may not know whether some of the young people in the group have personal experiences of gender-based violence, it is very possible that there are some survivors in the group. By fostering a culture of openness, respect and inclusion, facilitators create a safe space which can be inviting for young people to share negative/abusive experiences. Even though this is not very common, it is important that facilitators keep such a possibility at the back of their mind and they are prepared for it.

When disclosing abuse, young people may mention it matter of factly, suggesting some distancing from the experience or may become emotional, as the experience may still feel raw and painful. Any disclosure of abuse needs to be met with the necessary sensitivity and caring, as it takes a lot of courage on behalf of the young person to share something that makes them so vulnerable.

Make sure you have established ‘Ground rules’ (or a group agreement) beforehand, which call for confidentiality to be kept. This will likely prevent young people discussing the incidence with others, and helps protect the young person who has disclosed abuse from further exposure. Moreover, it is okay for the person to leave the room at any stage if they feel the need to, especially if they are getting too overwhelmed and need some space. If you are working with a co-facilitator, make sure you have agreed beforehand what to do if a young person discloses personal experience of abuse. It may be the case that one of you can offer to leave the room (physically or online) together with the young person if the young person wishes privacy to talk about things or just a little space.

It is also crucial to familiarize yourself with the policies on dealing with disclosure and on your legal obligations in relation to informing relevant authorities, especially in the case where the young person is under 18. For instance, if you have disclosure of abuse from a young person under 18, you may be obliged to inform the school management, the police, the social services, a specific organization/body that manages such incidences and can provide the right support etc. If you need to take action, it is vital you keep the young person fully informed of what is going on and ensure that your action does not put them at any further risk. In cases where a young person is living with domestic violence for example, contacting the abusive parent to discuss the disclosure is likely to put both the young person and the non-abusive parent at greater risk of abuse.

How to respond

- It is important not to ignore, interrupt or try to stop the young person while they are talking. However, if this is taking place in front of the group and the person is under 18, you need to protect them from any possible ‘exposure’ in front of the group. In this case, try to wrap up the discussion as early as possible, validating the person for sharing a difficult experience and for their courage to do so and recommend that you talk together after the session concludes. Remind the group that this is a safe space for sharing and that confidentiality is important (as per the group agreement). If the disclosure takes place from an older person (an adult), you can trust that they can set their own pace and comfort level in their disclosure.

- Make sure you hear the young person through as far as they are willing to go. Never push for more information, don’t ask probing questions and be mindful of getting curious.

- Validate their courage to share this difficult experience and thank them for trusting you and the group

- Validate that this is perhaps a difficult experience for them and mention that by talking about it they have already taken the first step in trying to rectify the situation. By talking about it, they are no longer alone in this and they can explore how to find support. There are many people and various services which can provide this support.

- Try to counteract their guilt and self-blame. Explain that nothing of what happened is their fault. This will also prevent the other young people falling into the trap and blaming the survivor for the abuse.

- If you feel it is appropriate and if the young person is okay with this, invite thoughts from the rest of the group, bearing in mind that this discussion needs to be facilitated closely and with sensitivity, so no negative comments are heard. Before comments are provided, remind the group of their mutual agreement of no-judgement, respect and confidentiality.

- Remember that it is not your job nor the responsibility of the group to act as therapists to the person who experienced the abuse. Irrespective of whether you have the skills or not, your responsibility is to only listen to the person, show empathy, make them feel valued and acknowledged, validate their feelings and guide them towards appropriate referrals where they can get further support.

- Pay special attention to the person who has made the disclosure of violence and make sure they are not left alone if they do not want to be. You or your co-facilitator might accompany them to another room (online or offline) to give them some space. They may need a short time away from the group, or alone.

- A good way to diffuse the situation if it is necessary (according to the overall vibe of the group at that stage) is to call for a short break and you can resume after 10 min.

- Before you end the workshop, make sure you have provided referrals where young people can turn to for support and that these are visible and available to all young people in the group.

Remember that when a young person discloses their experience of abuse, there are six things that they need to hear from someone:

- I believe you.

- I am glad you have told me this – you are very brave to have come forward.

- I am sorry this has happened to you.

- Unfortunately, gender-based violence is something that does take place and a significant share of young people are having similar experiences

- It is not your fault. Any experience of violence is never the fault of the person experiencing, but instead it is the responsibility of the person who is exercising the violence.

- You should not stay alone in handling this. There are people who can help.