● 4.1. What is meant by ‘groups at risk of social exclusion’[1]

Social exclusion goes beyond the issue of material poverty as it is also seen as encompassing other forms of social disadvantages such as lack of regular and equal access to education, health care, social care, proper housing. In general, any discrimination and/or denial of opportunities that prevents any group of people from fully exercising and enjoying their civil, social, economic, cultural and political rights is considered social exclusion[2]. Causes for exclusion encompass a wide range of reasons why individuals or groups might be excluded, such as discrimination against immigrants, ethnic minorities, the Roma, LGBTIQ+ persons, sex workers, people living with HIV, the disabled, the elderly, sex workers, etc. In short one can be socially excluded in a multitude of ways, for a multitude of reasons. Due to the multidimensional nature of social inclusion, it remains hard to interrelate these dimensions over time. The accumulation of a number of disadvantages may result in a self-reinforcing cycle that makes it difficult to attribute causality to one specific factor or another.

Social exclusion is context specific, as most nations have different interpretations of what it means to be socially excluded. Even within the EU, social exclusion has many definitions based on national and ideological notions of what it means to belong to society. These notions often differ from region to region, neighbourhood to neighbourhood and on an individual level as well. Moreover, social exclusion is understood not as a condition that is the outcome of a process, but as a process in itself. It is not static, but dynamic and different individuals or groups find themselves in different stages of the social exclusion process, be it only temporarily, recurrently or continuously.

Because of social structures and the hierarchies of power between the different groups in society some groups face particular vulnerabilities towards social exclusion. These vulnerabilities stem from social, cultural and physical characteristics such as race, ethnicity, sex, sexual identity, ability/disability and socio-economic status. A cross cutting vulnerability is gender and age, with young people and in particular young women and girls facing the highest risk for social exclusion worldwide[3]. The risk of adolescents and young adults to social exclusion is often misunderstood: it is often assumed that because young people are physically bigger, in contact with people outside their family and ‘moving towards independence’, they are less vulnerable than younger children. However, these assumptions about young people’s self-care skills, physical robustness, emotional development, resilience and need for independence can be misguided and sometimes harmful . For instance, while a young person may be able to disclose abuse or run from an abusive situation before they are badly injured, this does not prevent them from experiencing emotional harm. Nor does it protect them from the threats that can be created by their attempts to protect themselves (for example, a 16-year-old girl who ends up on the streets to escape from sexual abuse at home)[4]. When working with young people it is important not to underestimate their risk for vulnerability and social exclusion and take into account their need for protection, care, support and a sense of belonging.

● 4.2. Multiple vulnerabilities and intersectionality[5]

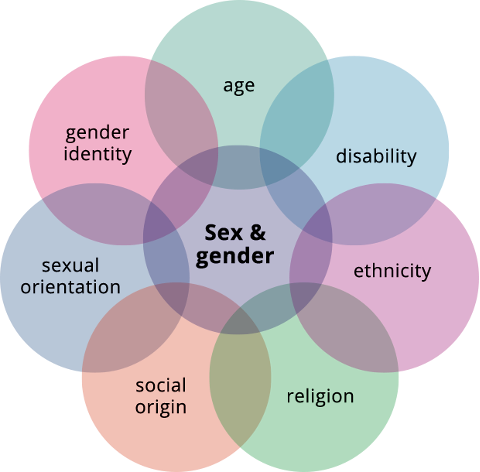

An important notion that arises when we are trying to fully understand vulnerability and social exclusion, is intersectionality. The theory of intersectionality posits that the various strands of social identity (such as ethnic background, race, gender, gender identity, gender expression, age, sexuality, (dis)ability, social class, religion etc.) do not exist independently, but interrelate in ways that create multidimensional identities and multidimensional experiences for people.

Intersectionality is often discussed alongside multiple discrimination. Multiple discrimination refers to a person being discriminated against at multiple levels in a single instance because of multiple characteristics; their multiple strands of identity intersect to create experiences of oppression that are multi-dimensional and unique for particular groups. The intersections between the different qualities/traits that make up a person’s identityare endless. For instance people can be lesbians who have minority ethnic backgrounds, gay and living in poverty, trans with a disability, bisexual and Muslim. Social, cultural and physical/biological characteristicsintersect on multiple and simultaneous levels and it is this interaction that reinforces the oppression each one brings, resulting in multiple levels of discrimination and multiple levels of oppression.

Thus, the harmful impact of sexism, homophobia, biphobia, transphobia, interphobia, gender-based violence, sexual and intimate partner violence can be more impactful for certain individuals due to their ethnicity, age, disability, social origin, religion, gender identity, sexual orientation or other factors and the ways these different identities intersect with each other. Moreover, the more intersections a person experiences, the more likely it is to experience less avenues to protection and safety from SGBV, as exit strategies or access to services, justice and redress may be compromised in lieu of social stigma, discrimination, isolation, marginalization, retribution and even persecution on account of certain identities. The experience of a migrant woman experiencing sexism, for instance, is very different from the experience of a white woman who also experiences sexism but is part of the dominant culture; the experience of the first one is different because it stands on the crossroads between racism and sexism, both of which are experienced at the same time. Consequently a migrant woman may have compromised access to information on how to recognize sexism, more limited access to services for support and more limited protection by the police, on account of institutional discrimination and violence.

The constant interaction of intersections, however, is complex and does not always end up with a predictable result. In some cases one intersection might cancel out another, while in other cases, one leads to discrimination and another results in privilege. This complexity is important to take into consideration when working with intersectionality and we need to recognize that people– in all their diversity – should enjoy respect, and celebrate all the intersections of their identity. An intersectional approach recognizes that these multiple intersections exist in endless combinations, and that they can sometimes lead to privilege and sometimes to discrimination.

● 4.3. How does SGBV affect certain vulnerable groups?

Women, children, older people, LGBTIQ+ individuals, migrants, individuals that belong to ethnic minorities, Roma, sex workers, people living with HIV and people with disability are particularly vulnerable to experiencing SGBV. For the purpose of this toolkit, we are focusing on how SGBV affects 4 key vulnerable groups, LGBTIQ+ persons, Roma, sex workers and people with disability.

LGBTIQ+ persons[6]

The LGBTIQ+ acronym stands for lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans, intersex and queer identities, while the + sign suggests that the term is inclusive of all identities with diverse emotional/sexual attractions, sexual orientations, gender identities/expressions and sex characteristics. The LGBTIQ+ community does not comprise of a homogenous group and different members of this community may experience different vulnerabilities and different types and degrees of violence, with trans people being considered to be the most vulnerable group within LGBTIQ+ communities. Heteronormative perceptions and heterosexism often result in prejudice, intolerance, discrimination, marginalization and violence against LGBTIQ+ persons, which can even lead a to hate crimes against them.

While the majority of people are aware of frequent inappropriate jokes, comments and microaggressions against LGBTIQ+ people, little awareness exists in the public eye about serious existential problems and violence that the LGBTIQ+ population is experiencing and LGBTIQ+ individuals themselves may refrain from disclosing their experience of violence due to fear of reprisals, stigma and discrimination.

Schools are particularly hostile spaces for LGBTIQ+ youth, with only a very small of share of them (4%) [7]considering school as a safe space. As a result, more than two thirds of LGBTIQ+ students (67%)[8] admit that they feel forced to hide their sexual orientation and/or gender identity at school. This data is also supported by GLSEN’s The 2017 National School Climate Survey[9] which reveals that young people who are known to be lesbian, gay or bisexual go through significantly more verbal and psychological violence from their peers, but also their parents and other adults, such as teachers. Experiences of trans adolescents (or more generally speaking, those with non-normative gender identities) are even more complex because they often suffer manifold discrimination, they are pathologized by experts and face an even more extreme isolation. Peer violence over young LGBTIQ+ persons often lasts for a long time; they become targets of organized peer attacks daily, so they are frequently forced to change or leave schools.

Teachers and other members of school staff often do not have the awareness or skills to respond to incidences of homophobic/transphobic/interphobic bullying or may refrain for intervening as they often believe that LGBTIQ+ students are partly responsible for the violence they experience[10]. The violence, verbal bullying and the threats of physical violence LGBTIQ+ young persons are subjected to, are a source of great stress and have a significant negative impact on their mental health.

Violence towards LGBTIQ+ youth is often related to negative outcomes, such as problems in school, lower academic achievements, school absenteeism, the use of psychoactive substances, conflicts with the legal system and suicide. According to the Council of Europe’s survey (2018) ‘Safe at school’, LGBTIQ+ students are between 2 and over 5 times more likely to think about or attempt suicide than their heterosexual peers. An additional study from Ireland which included intersex students, found that students aged 14–25 who experienced bullying based on their LGBTIQ+ identities were more depressed, anxious and stressed, and had lower self-esteem than others[11]. As a result, for many LGBTIQ+ students spending time in school does not mean studying, but instead a literal fight for survival and it represents a strong traumatic experience.

Social discrimination and SGBV against LGBTIQ+ persons also expand in all social environments besides schools, including, among others, the labour market, the work environment, state institutions, healthcare, their own families and intimate relationships. Inter alia, LGBTIQ+ persons often experience discrimination when trying to enter the labour market; are the recipients of aggressions, bullying and harassment at work and/or exclusion and isolation from colleagues; face significant barriers in accessing healthcare services or experience psychological abuse, stigma or harassment by medical personnel and are often the recipients of police aggression or brutality. Institutional violence, combined with lacking policy and legal frameworks or lack of implementation of existing laws and regulations, greatly hinders LGBTIQ+ individuals seeking support and protection and their overall access to justice.

LGBTIQ+ persons also experience domestic violence within their biological families, including lack of respect of their identity, stigma, exclusion and isolation, psychological violence and physical violence. Similarly, they experience intimate partner violence in all forms and manifestations (physical harm, coercive control, psychological violence, humiliation, threats to ‘out’ them, stalking, harassment, verbal abuse, sexual violence etc.). Notably, because of their identities, LGBTIQ+ persons encounter significant barriers in accessing domestic violence or IPV related services due to fear of identity disclosure, stigma, discrimination, persecution etc.

In addition to the different forms of SGBV described above, additional questions arise in the case of LGBTIQ+ persons concerning the right to marriage, adopting children, and the rights of same sex families. Same sex unions are not recognized as equitable unions in many European countries or are not recognized as unions at all, with same sex couples having no access to benefits that heterosexual couples enjoy (for instance inheritance after the death of a partners, the right to make medical decisions in the name of their partner, access to social benefits or welfare). In few European countries LGBTIQ+ persons have the right to adopt children while rainbow families[12] experience severe marginalization and exclusion.

Because of prejudice and discrimination, LGBTIQ+ persons are often forced to keep their relationships a secret. They refrain from openly talking about their relationships, speak about their partner with peers, take their partner to a family dinner or party. For LGBTIQ+ persons such ‘disclosures’ are often risky. LGBTIQ+ people who are open about their identity risk experiencing psychological and physical violence in the streets, are being fired from work or denied employment, are evicted or refused housing, are isolated, excluded, rendered invisible and marginalized in many different ways.

The lack of positive LGBTIQ+ models, and their depictions as sinful, immoral and outcast members of society can also lead to internalization of these social stereotypes, resulting in feelings of shame and low self-worth. Internalized heterosexism also leads to LGBTIQ+ individuals building a negative image about themselves, feelings of confusion, helplessness and isolation, escalating sometimes to serious mental issues (suicidal thoughts, depression etc.)

The most serious forms of violence LGBTIQ+ persons experience include hate crimes, which include verbal abuse and harassment, hate speech, intimidation, threats, assault, damage to property, corrective rape and even death. However, homophobic and transphobic violence remains significantly underreported across Europe with fewer than one in five of the incidents (17%)[13] being brought to the attention of the police, raising significant questions as to the safety and protection of the LGBTIQ+ community from SGBV.

Roma women [14]

Romani women are significantly subordinated to men within the Roma patriarchal family system. Nonetheless, relations between men and women differ according to groups and nationalities. In most of the Roma communities, however, young women’s choices are overdependent on family and communities’ rules and interests. The Roma patriarchal family model affects Romani women’s access to basic human rights and exposes them to many different forms of discrimination and violence, including:

- Low education levels and high financial dependability: Romani women are overloaded with family responsibilities at an early age. Early marriage affects girls’ school attendance, undermining their right to education and limiting their future employment opportunities. Particularly low socio-economic conditions and low educational achievements bring about utter dependency on men (fathers, brothers, partners , sons etc) and enhance the vulnerability for young Roma women to violence including IPV and domestic violence.

- Risk of trafficking and sexual exploitation: The low socio-economic conditions also significantly increase the risk for trafficking and sexual exploitation. Roma are estimated to represent between 50 and 80 % of trafficking victims in Eastern European countries[15].

- Restriction of freedoms and control of women’s bodies: in traditional patriarchal Roma communities, young women are barred from public life and often cannot leave their communities without being watched by other family members. Virginity of the girl and preservation of chastity are very important for the honour of all family members and evidence of preserved virginity are publicly shown and specially celebrated during wedding celebrations.

- Early (forced) marriage and motherhood and women’s subordination to the family: Arranged (and forced) marriage and child marriage are common practice, accepted by Roma women. For an arranged marriage, the Roma girl comes at a price and her parents receive a considerable lump sum of money from the boy’s family. The young bride is usually expected to live in her husband’s parents’ house and to accept without objection the order and the power of her mother-in-law and her husband there. It is considered a serious offence by the young wife to disobey to the slightest extent her mother-in-law’s requirements on domestic and care responsibilities, often resulting in physical or psychological abuse, both by the mother-in-law and the husband. The young bride is expected to become pregnant and give birth as soon as possible. Delay of pregnancy may be used as a ground for dissolution of marriage and expulsion of the girl. Early marriage affects girls’ school attendance, undermining their right to education and consequently resulting to low socio-economic conditions, further enhancing their marginalization, social exclusion and vulnerability to violence.

- Institutional violence: Overall, there is great mistrust of the Romani communities in non-Roma law and state agents, partly as a result of past persecutions (including policies of extermination and resettlement) and current racial discrimination, stigmatization, violence and state indifference or brutality to protect the rights of the Roma population. State policies of forced sterilization had constituted a gross violation of women’s rights in Central and Eastern Europe. Between 1971 and 1991 in Czechoslovakia, now Czech Republic and Slovakia, state policies sanctioned the “reduction of the Roma population” through surgical sterilization. The sterilization would be performed on Romani women without their knowledge during Caesarean sections or abortions[16].

- Intimate partner violence and domestic violence: Intimate partner violence is socially accepted within some Roma communities as an endorsed exercise of men’s power over women. In societies where there is little tolerance for Roma people in general, exit strategies or avenues to protection and safety from intimate partner violence often become scarce, enhancing Romani women’s vulnerabilities to SGBV.

On one hand, certain traditional values may add to the obstacles Romani women face when they need to access protection and justice. Domestic violence is hardly talked about because it constitutes a social taboo. Sexual violence is an even bigger taboo and discussions on topics that relate to sexual matters are strictly avoided. Women who experience sexual violence before they are married are considered ‘impure’ and a disgrace to the family’s honour. This significantly enhances their risk to honour-based violence. Even if Romani women try to get justice about intimate partner violence or sexual violence, they have to go through the ‘kris’, an internal system of public tribunal or court, which regulates all civil and criminal disputes including adultery and acts of violence. However, in lieu of traditional norms and values that condone gender-based violence, the kris exhibits substantial shortcomings in protecting Romani women’s rights.

On the other hand, there is an evident lack of trust to non-Roma law and state agents primarily due to the discrimination, stigma, persecution, and institutional violence exercised by authorities themselves, which often restricts avenues to protection and safety and results in many Romani women suffering in private and having limited means of breaking the cycle of violence.

Sex workers[17]

Sex workers face high levels of violence, discrimination and other human-rights violations because of the stigma associated with sex work (which is criminalized in most settings), or due to discrimination based on gender, gender identity, sexual orientation, race, ethnicity, HIV status, drug use or other factors. Most violence against sex workers is a manifestation of gender inequality and discrimination directed at women, or at men and trans individuals who may not conform to gender and heterosexual norms.

Sex workers experience all forms of SGBV, including physical, psychological, sexual, socio-economic and institutional. Moreover, additional human-rights violations that need to be considered in conjunction with violence against sex workers also include:

- having money extorted

- being denied or refused food or other basic necessities

- being refused or cheated of salary, payment or money that is due to them

- being forced to consume drugs or alcohol

- being arbitrarily stopped, subjected to invasive body searches or detained by police

- being arbitrarily detained or incarcerated in police stations, detention centres and rehabilitation centres without due process

- being arrested or threatened with arrest for carrying condoms

- being denied the use of contraception or being forced to have sex without the use of a condom, increasing their susceptibility to sexually transmitted infections

- being refused or denied health-care services

- being subjected to coercive health procedures such as forced STI and HIV testing, sterilization, abortions

- being publicly shamed or degraded (e.g. stripped, chained, spat upon, put behind bars)

Contexts of violence There are several contexts, dynamics and factors that enhance sex workers’ vulnerability to violence.

- Workplace violence: This may include violence from managers, support staff, clients or co-workers in establishments where sex work takes place (e.g. brothels, bars, hotels).

- Violence from intimate partners and family members: Stigmatization of sex work may lead partners or family members to think it acceptable to use violence as punishment. It may be difficult for sex workers to leave an abusive relationship, particularly when their abusers have control over them due to ownership of a home, or the power to harm or refuse access to their children. Sex workers- particularly female and trans sex workers who survive IPV or domestic violence, have no access to services because of fear or persecution, discrimination, stigma or issues about law enforcement- such as police refusing to take record of their complains or being indifferent to intervene to protect them. In turn, this makes them more vulnerable to IPV and domestic abuse.

- Violence in public spaces: In most contexts, the antagonistic relationship with police creates a climate of impunity for crimes against sex workers that may lead them to be the targets of violence or of other crimes that may turn violent, such as theft. Sex workers may also be targeted by abusers who want to “punish” them in the name of upholding social morals, or to scapegoat them for societal problems, including HIV. Sex workers may also face violence from individuals in a position of power on whom they may depend for the provision of services, e.g. nongovernmental organizations (NGO), health-care providers, bankers or landlords.

- Organized non-state violence: Sex workers may face violence from extortion groups, militias, religious extremists or “rescue” groups.

- State violence: This includes manifestations of violence, intimidation and sexual exploitation that is directed to sex workers from military personnel, border guards and prison guards, and most commonly from the police. Violence by representatives of the state compromises sex workers’ access to justice and police protection, and sends a message that such violence is not only acceptable but socially desirable. Criminalization or punitive laws against sex work increase sex workers’ vulnerability to violence as they often provide cover for violence and sexual exploitation by the police. For example, forced rescue and rehabilitation raids by the police in the context of antitrafficking laws may result in sex workers being evicted from their residences onto the streets, where they may be more exposed to violence. Similarly, laws and policies that discriminate against trans individuals and men who have sex with men (such as not recognizing abuse towards them as a criminal act and refusing to respond to such complains) substantially increase their vulnerability to abuse.

Fear of arrest, retribution, harassment and aggression by the police remains a key barrier to sex workers reporting violent incidents. Even where sex work is not criminalized, the application of administrative law, religious law or executive orders may be used by police officers to stop, search and detain sex workers. This also often forces street-based sex workers to move to locations that are less visible or secure, or pressure them into hurried negotiations with clients that may compromise their ability to assess risks to their own safety. - Compromised access to services: Sex workers are also made more vulnerable to violence by their compromised access to services. Some may have little control over the conditions of sexual transactions (e.g. fees, clients, types of sexual services) if these are determined by a manager. The availability of drugs and alcohol in sex work establishments increases the likelihood of people becoming violent towards sex workers working there. Sex workers who consume alcohol or drugs may not be able to assess situations that are not safe for them. Violence or fear of violence may prevent sex workers from accessing harm reduction, HIV prevention, treatment and care, health and other social services as well as services aimed at preventing and responding to violence (e.g. legal, health). Discrimination against sex workers in shelters for those who experience violence may further compromise their safety.

People living with disability

People with disabilities face a heightened risk of domestic and sexual violence because of stigma, discrimination and low regard ( i.e. perceptions of them as weak, less productive members of society and of considerably lower social status). For disabled people, and particularly women with disability, the intersections of gender-based violence and disability discrimination constitute severe barriers to well-being. Women with disability are in a significantly more vulnerable position compared to their male counterparts as they experience much higher levels of physical, sexual, and psychological violence, for longer periods of time and with worse physical and mental outcomes.

The following factors significantly contribute to the additional vulnerability of people with disabilities towards SGBV[18]:

Patriarchal attitudes: Attitudes towards women and people with diverse gender identities and sexual orientations in patriarchal societies combined with vulnerabilities related to the disability itself, create multiple vulnerabilities and significantly increase the risk for multiple layers of violence.

Powerlessness: People with disabilities are less able to defend themselves or seek support because of their isolation e.g. they may be hidden away, the nature of disability leaves them isolated, or they may not recognise that what is happening is unacceptable and not their fault.

Barriers in accessing services: These include lack of access to information (and education in some cases), healthcare, legal protection and redress, either because these services do not cater for disabled people’s special needs in terms of access and provision of services or because there is lack of awareness of the issues that people with disabilities face in regard to their vulnerability.

Disability-based gender-based and sexual violence manifests itself at physical, psychological, sexual, economic and institutional levels. Abuse and discrimination of persons with disabilities by medical professionals is commonplace. What is often masked as “good intentions” are, in fact, acts of serious discrimination and violence: as in the case of intrusive and irreversible medical treatments without informed consent or in cases where appropriate treatment is withheld (in the context of HIV/AIDS for instance) based on disability-related prejudice and misconception[19] . Myths about the sexuality of disabled persons also violate their rights. People with physical or sensory impairments are often wrongly deemed asexual. Women with intellectual or mental disabilities are seen as oversexed. These stereotypes can lead to forced and/ or coerced sterilisation to avoid pregnancies or forced/coerced abortions because women with disabilities are deemed incapable of being mothers , or because the suppression of their menstruation is easier to manage for their carers.

Many people with disability lack access to information about their sexual and reproductive rights. This lack of information about rights, services and programmes makes it harder for people with disabilities to negotiate relationships and increases their risk of intimate partner violence and HIV/ STIs transmission.

Women with disability in particular are considerably more vulnerable to sexual violence, by carers, family members and intimate partners, on all of which people with disabilities heavily depend on. International studies cited by the Working Group on Violence Against Women with Disabilities, ‘Forgotten Sisters’ (2012)[20]indicate that women with disabilities suffer up to three times greater risk of rape, by a stranger or acquaintance, than their non-disabled peers.

Women with disabilities also experience much higher levels of family violence. Consistent exposure to insults; belittlement; physical abuse; wilful neglect, being left isolated for long periods of time as punishment, or left unassisted for mobility or personal hygiene; and constant lack of respect throughout the life cycle can have serious effects and negative mental outcomes. Frequently considered as a burden by their families they are also either rejected or hidden away, making them invisible in their communities, further enhancing their social isolation and consequently their vulnerability to violence.

- Source: The INCLUSO Manual (2010). Program funded by the 7th Framework program of the EU. Available for e-reading at http://www.incluso.org/manual

- .

- Panos Tsakloglou & Fotis Papadopoulos (2002). Identifying Population Groups at High Risk of Social Exclusion: Evidence from the ECHPR. In Muffels, P. Tsakloglou and D. Mayes (eds.). Social Exclusion in European Welfare States. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar, pp. 135-169

- Adapted from ‘Practice Paper: A framework for practice with ‘high-risk’ young people (12-17 years)’ Queensland Government: Department of Child safety, youth and women. December 2008

- Adapted from ‘Norm-criticism Toolkit’, IGLYO (2016)

- Source: Manual For Youth Workers: Raising Capacity In Working With LGBT+ Youth. Association RAINBOW, Serbia, 2017

- FRA(2017). EU LGBT Survey

- FRA(2017). EU LGBT Survey

- GLSEN (2019). The 2017 National School Climate Survey: The Experiences of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer Youth in Our Nation’s Schools. https://www.glsen.org/research/school-climate-survey

- GLSEN (2019).

- Council of Europe (2018): Safe at school: Education sector responses to violence based on sexual orientation, gender identity/expression or sex characteristics in Europe.

- Rainbow families refer to same-sex or LGBTIQ+ parented families, i.e. to parents who define themselves as LGBTIQ+ and have a child (or children) , are planning to have a child (either by adoption, surrogacy or donor insemination etc) or are co-parenting

- OSCE Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights, ODIHR reporting https://www.osce.org/odihr

- Adapted from the report Empowerment of the Roma women within the European Framework of National Roma Inclusion Strategies’ . European Parliament’s Committee on Women’s Rights and Gender Equality (2013)

- ERRC (March 2011): Breaking the silence. A report by the European Roma Rights Centre and People in Need. Trafficking in Romani Communities http://www.errc.org/cms/upload/file/breaking-the-silence-19-march-2011.pdf

- European Women Lobby – references in Hungarian background report.

- Source: WHO (2013). Implementing Comprehensive HIV-STI Programmes: Addressing Violence against Sex Workers. https://www.who.int/hiv/pub/sti/sex_worker_implementation/swit_chpt2.pdf

- Source: ADD International (2016). Disability and Gender-Based Violence. ADD, International: Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. https://add.org.uk/file/2933/download?token=kg-SOlvo

- Andrae Karen (2013). Disability and Gender-based violence. ADD international’s approach. A learning paper. ADD International: UK.

- Ortoleva, Stephanie and Lewis, Hope (2012). Forgotten Sisters – A Report on Violence Against Women with Disabilities: An Overview of its Nature, Scope, Causes and Consequences . Northeastern University School of Law Research Paper No. 104-2012, Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2133332