● 3.1. Definition of sexual and gender-based Violence

Sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV) refers to any violent act that is perpetrated against a person’s will and is based on gender norms, norms about sexual orientation and unequal power relationships (UNCHR definition). It can be physical, emotional, psychological, or sexual in nature, and also encompasses threats of violence, coercion and/or coercive control. Gender-based violence is often normalised and reproduced due to structural inequalities, such as societal norms, attitudes and stereotypes that surround gender and violence against women. Towards this end, structural or institutional violence may also arise, expressed as the subordination of women and LGBTIQ+ persons in economic, social and political life.

SGBV affects women, girls, men, boys, LGBTIQ+ persons and other people with diverse Sexual Orientations, Gender Identities and Expressions and Sexual Characteristics (SOGIESC). SGBV is considered to be a gross violation of human rights as it denies human dignity and hinders human development[1].

Some useful definitions also include[2]:

Gender-based violence

The term gender-based violence is used to distinguish common violence from violence that targets individuals or groups of individuals on the basis of their gender, sex, sexual characteristics, gender identity/expression and sexual orientation or perceived gender, sex and gender identity. Gender-based violence (GBV) can take many forms and ranges from its most widespread manifestation, intimate partner violence, to acts of violence carried out in online spaces. These different forms of GBV are not mutually exclusive and multiple incidences of violence can be happening at once and reinforcing each other. Intersecting inequalities experienced by a person related to their race, (dis)ability, age, social class, religion, gender identity, gender expression and sexuality can also drive acts of violence. This means that while people face violence and discrimination based on their gender, some experience multiple and interlocking forms of violence[3].

Sexual violence

According to the United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights[4], sexual violence is a form of gender-based violence and encompasses any sexual act, attempt to obtain a sexual act against a person’s consent. Violation of consent is a way in which a perpetrator exerts power over another. This also includes unwanted sexual comments or advances, acts to traffic, or any acts otherwise directed against a person’s sexuality by any person regardless of their relationship to the person experiencing the sexual violence, in any setting. Sexual violence takes multiple forms and includes rape, marital rape, attempted rape, sexual abuse, sexual harassment, sexual exploitation, non-consensual pornography, sextortion, sexualised bullying, forced pregnancy, forced sterilization, forced abortion, forced sex work, trafficking, sexual enslavement, forced circumcision, female genital mutilation and forced nudity.

Violence[5]

Violence is a means of control and oppression that can include emotional, social or economic force, coercion or pressure, as well as physical harm. It can be overt, in the form of physical assault or threatening someone with a weapon; it can also be covert, in the form of intimidation, threats or other forms of psychological or social pressure. The person experiencing violence is compelled to behave as expected or to act against their will out of fear. Violence can be an act or a series of harmful acts exercised by a single person towards another, or by a group of people against a single person, or against a group of individuals.

The difference between violence and abuse

Even though violence and abuse are often used interchangeably (and in most parts of the toolkit this is also the case) there are some differences between abuse and violence that are worth considering, especially when used in the context of intimate partner violence. Abuse occurs when a person’s words, behaviour and actions are intentionally aimed at hurting another person. If certain behaviours negatively influence, restrict or stop a person from making choices over their own body, their wellbeing and their life or if these behaviours actually take control over another person’s body, wellbeing or life, then these behaviours are abusive. Abuse turns into violence when the unhealthy behaviour is more systematic and a combination of abusive, degrading, hurtful behaviours are used. Abuse becomes violence when it causes a person to lose all feeling of safety and start fearing for their life. Violence impacts every aspect of our wellbeing—physical, emotional, spiritual and mental.

Coercion

Coercion is forcing, or attempting to force, another person to engage in behaviours against their will by using threats, verbal insistence, manipulation, deception, cultural expectations or economic power.

Victim/survivor[6]

The term victim(s)/survivor(s) refers to individuals or groups who have suffered sexual and gender-based violence. Increasingly, people who have experienced/suffered SGBV are referred to as survivors, in an effort to recognize their strength and resilience and to avoid any implied or unintended messages of powerlessness or stigmatization. However, in certain legal contexts, the term victim may be more appropriate and/or required to conform to relevant laws when seeking legal redress. In reality, it is up to the person to describe how they feel, and sometimes people who have experienced violence feel like the term “victim” matches how they feel better. To recognize all of these contingencies, usually both terms are used. In this toolkit, the term ‘person experiencing violence’ has been used instead to avoid any negative connotations related to other terms.

Perpetrator/offender

According to EIGE’s definition, a perpetrator[7] is a person who deliberately uses violent and abusive behaviour to control their partner or former partner, whether or not they have been charged, prosecuted or convicted. The term ‘sexual violence offender’ can also be used to describe male perpetrators of sexual violence, especially in the context of legal persecution and justice systems. In other contexts, perpetrator is used to describe males who commit domestic and family violence against women or children[8]. Because of the different meanings of the term, none of which are all encompassing, the term used in this toolkit is ‘person exercising the violence’ as a means to label the behaviour rather than the person and avoid any stigmatization that may come with the term perpetrator.

People who exercise violence are in a position of real or perceived power, decision-making and/or authority and can thus exert control over the person they abuse[9]. These may include current or ex- intimate partners, current or ex-spouses, family members, close relatives, colleagues, classmates and peers. Moreover, they may include people in a position of influence or power such as politicians, bosses, teachers, community and spiritual leaders.

Perpetration of violence may also take place by institutions, in the context of institutional violence. Withholding information, delaying or denying medical assistance, discriminatory practices in the delivery of social services, offering unequal salaries for the same work and obstructing justice are some forms of violence perpetrated through institutions. During war and conflict, sexual and gender-based violence is also frequently perpetrated by armed members from warring factions.

Notably, the overwhelming majority of cases of sexual and gender-based violence are committed against women by men. Most acts of sexual and gender-based violence against boys and men are also committed by men.

● 3.2. What gives rise to SGBV?

Normalized beliefs about gender, toxic/hostile masculinity and attitudes of tolerance that condone violence

Hagemann-White et al (2010), identify various factors which increase the likelihood of gender-based violence being perpetrated, tolerated and even considered acceptable. The factors include:

- Gender inequality, underpinned by normative beliefs about the proper spheres of women and men, the relative value of these spheres in society, and the legitimate distribution of power between women and men in each sphere.

- Traditional, rigid gender concepts of masculinity, associating masculinity with control, dominance and competition and femininity with caring and vulnerability. In addition, norms and structural inequalities granting men control over women and the decision-making power over political and economic resources.

- The portrayal of stereotypes about men and women in popular media and the depiction of violent actions as rewarding and successful, while sexualizing violence and portraying women as available and vulnerable sexual objects.

- Tolerant attitudes that condone violence and acceptance of violence as a way to resolve conflict.

- Peer groups (especially in adolescence) supporting sexist behaviour or violence and reinforcing hostile masculinity and aggression.

- The failure of agencies to sanction gender-based violence, for example teachers ignoring incidents of gender-based bullying at school, low persecution rates of people exercising SGBV by the justice system, police brutality towards people with diversity in SOGEISC

Patriarchy and male privilege[10]

The notion of patriarchy is often used as an “abbreviation” for the dominance of men in society. As members of the dominant group, men enjoy significant privileges, such as more freedom and independence, higher salaries, professional development, positions of greater power and generally have more prestige, dominance and control. Men learn that specific privileges and advantages rightfully belong to them and they expect that women and people belonging in other groups (such as LGBTIQ+ individuals for instance) will compromise or submit accordingly. Most modern societies could be considered patriarchal or male-dominated, which is reflected in the fact that main institutions (such as political parties, governments, businesses, the education and health sectors, the media etc.) are, for the most part, controlled by men.

In patriarchal societies, however, not all men enjoy the same privileges as there are hierarchies among men, which are defined by their social and financial status, religion, origin, educational level, sexual orientation, age etc., and which are guarded by exercising violence and bullying. For example, a well-educated, white, heterosexual man who enjoys high economic status has greater power and prestige than a migrant, homosexual man of a lower socioeconomic status.

Power[11]

Power is understood as the capacity to make decisions. All relationships are affected by the exercise of power. When power is used to make decisions regarding one’s own life, it becomes an affirmation of self-acceptance and self-respect that, in turn, fosters respect and acceptance of others as equals. When used to dominate, power imposes obligations restricts, prohibits, and makes decisions about the lives of others.

Power can only exist in relation to other people and is something that a person may not always have. Having power means being able to have access to and control over resources and to be able to freely engage in decision-making. In patriarchal societies men have the power as they have more access, opportunities and control of resources (decision-making and political power, more leadership positions, more money, better jobs etc.). Hierarchies of power within societal structures arise from:

- Gender Stratification: The uneven distribution of wealth, power and privileges between the different genders.

- Sexism: The conviction that the male gender is innately superior to women and essentially all other expressions of gender.

- Institutionalized Sexism: When the institutions of a society operate in a sexist manner, resulting in discrimination and the denial of equal opportunities and rights to everyone.

- Patriarchy: Patriarchy as a system of social structures and practices, whereby men dominate, oppress and take advantage of women and other groups.

When discussing power, it is important to identify how different dynamics of power come into play. Toward this end, it is worthy to explore notions of the ‘power over’, the ‘power to’, the ‘power within’ and the ‘power with’.

- Power over means enjoying more privileges than others. It also means having control and domination of someone else. The dominant groups (heterosexual, white men in patriarchal societies) have power over other groups, which have historically been excluded, isolated and marginalized (women, LGBTIQ+ persons, individuals that belong to ethnic minorities, people with disability etc.).

- Power to is the ability to influence your own life by having the knowledge, skills, money or even just the drive and motivation to do something. We all have the power to, even though at times we may not be able to express it. For example, a young woman who was not allowed to continue her formal schooling, still has the ability learn by taking advantage of opportunities of non-formal education. To bring social change, it is important that people recognize their power-to.

- Power within refers to the internal power each person has and ultimately refers to a person’s sense of self, self-worth, self-confidence and self-esteem. It refers to the power within each individual to believe in themselves, their strengths and their abilities; the power to create change, to strive for a better life and assert one’s rights.

- Power with is the power you have with others, as a group – e.g., the collective power of young people to take decisions and action on areas of common ground or interests that benefits all.

It is important to recognize and acknowledge that individuals and groups that have historically been marginalized often have little power to influence much and tend to develop a strong sense of powerlessness. Focusing on how to harness the power within (and diminish the feelings of powerlessness) while acknowledging the limited power over and power to is important, by inspiring these groups to engage more in the power with. Our ultimate goal is to inspire young people to recognize the power within them and use that for the power to build knowledge and create change by harnessing this power with others and ultimately have a positive impact on and power over their lives and their community.

● 3.3. Different manifestations of SGBV

SGBV can be manifested in many different forms, all of which have very negative effects on the lives of the persons who experience the violence. It can be physical, emotional, psychological, or sexual in nature. Intimate partner violence remains the most widespread form of gender-based violence worldwide. Other forms include domestic violence, socio-economic violence, structural or institutional violence, honour-based violence, harmful cultural practices and femicide.

SGBV takes place in different spaces and contexts, such as:

- At home (i.e. domestic violence, intimate partner violence, sexual abuse by an intimate partner, honour-related violence, harmful cultural practices etc.)

- At school (e.g. school based SGBV, sexualised bullying, homophobic/transphobic/biphobic and interphobic bullying)

- At the place of employment (e.g. harassment, bullying, sexual harassment)

- At public spaces (stalking, harassment, bullying, sexual assault, rape, intimate partner violence)

- At institutions (e.g. institutionalized gender-based violence such as at health services, social services, judicial and legal services, police)

- Online (e.g. cyberbullying, online harassment, non-consensual pornography, revenge porn, sextortion, cyberstalking, online coercive control, online emotional abuse)

Definitions and more detailed explanations of the various forms of GBV are included below. The different forms of sexual violence are outlined in the definition of sexual violence in section 3.1 above and are explained in more detail in section 12.1.

Physical abuse[12]: Physical abuse is the use of physical force against another person in a way that ends up injuring the person, or puts the person at risk of being injured or killed. Physical abuse ranges from physical restraint to murder. Physical abuse includes: pushing, throwing, kicking, slapping, grabbing, hitting, hair-pulling, punching, beating, battering, bruising, burning, choking, shaking, pinching, biting, restraining, confinement, destruction of personal property, throwing things at, assault with a weapon such as a knife or gun and murder.

Emotional and psychological abuse[13]: Mental, psychological, or emotional abuse can be verbal or nonverbal. Verbal or nonverbal abuse consists of more subtle actions or behaviours than physical abuse. While physical abuse might seem worse, the scars of verbal and emotional abuse are equally deep, or even deeper. Emotional and psychological abuse includes, but it is not limited to:

- threatening or intimidating to gain compliance

- violence to an object (such as a wall or piece of furniture) or pet, as a way of instilling fear of further violence

- frequent yelling at or screaming

- name-calling, insults, use of derogatory names

- inducing fear through intimidating words or gestures

- controlling behaviour and coercive control

- constant harassment, offline and online

- making fun of and mocking, either in private, in public, in front of family or friends and in social media

- criticizing or diminishing the other person’s accomplishments or goals

- making the other person feel bad about themselves and that they are worthless

- excessive possessiveness, confinement, isolation from friends and family

- excessive checking-up (through phone-calls, texts, instant messaging, social media accounts)

- manipulation

- ultimatums and coercion

Coercive control and controlling behaviours: monitoring the partner’s movements; restricting access to friends, social media, socialization, financial resources, employment or education; control of the partner’s sexuality; any oppressive tactics which repeatedly aim to make the partner feel controlled, dependent, isolated or scared and which aim to intimidate, degrade and have power over the other person.

Stalking: Stalking involves any unwanted repeated contact that makes a person feel scared or harassed. Stalking can take place both online (cyberstalking) and offline and is perpetrated by a partner, ex-partner, an acquaintance or by someone who is unknown to the person experiencing the stalking. Some examples include:

- excessive checking-up on the other person, both online and offline either by following them around or by calling, texting or using social media to constantly reach them

- spying

- showing up uninvited at the other person’s house, school, or work

- leaving unwanted gifts for the other person

- sending unwanted, frightening, or obscene emails, text messages, or instant messages

- tracking the other person’s computer and internet use

- using technology (GPS, apps etc.) to track where the other person is

Bullying: Bullying involves any behaviour that aims to intimidate, hurt, or affect a person’s physical or psychological well-being, is systematic, repetitive, and involves a power imbalance between the individuals involved. Bullying can occur directly (towards specific people) or indirectly (by instigating rumours or accusations about certain people, without them being present). Bullying can also be manifested online (cyber bullying) through social media, cell phones, email and websites. Bullying can take various forms, including but not limited to teasing, derogatory comments, humiliation, ridicule, mockery, harassment, threats, social isolation, verbal and physical assault and death threats.

Homophobic/transphobic/interphobic bullying is bullying that takes place due to prejudice or negative attitudes, beliefs or opinions against people with diverse sexual orientations, gender identities/expressions and sex characteristics. People at the receiving end of this type of bullying include people who may not conform to gender norms or heteronormative social expectations, are diverse in their SOGIESC, are perceived to be LGBTIQ+, belong to rainbow families[14] or appear to be ‘different’ in some way.

Hate crimes[15]: Hate crime generally refers to criminal acts which are seen to have been motivated by extreme bias, prejudice and hatred against specific social groups (such as LGBTIQ+ persons or people with diverse Sexual Orientations, Gender Identities and Expressions and Sexual Characteristics). Incidents may involve physical assault, damage to property, bullying, cyberbullying, harassment (online and offline), verbal abuse or insults, offensive graffiti, hate mail, online hate speech and even murder. Killings of LGBTIQ+ persons on the grounds of being LGBTIQ+ and ‘corrective rape’ of LGBTIQ+ persons constitute the ultimate forms of hate crimes.

Intimate partner violence[16]: Intimate partner violence is the violence against a person by the current or ex-partner or the person that the individual experiencing the abuse is or has been in an intimate relationship. Intimate partner violence (IPV) constitutes a pattern of abusive and threatening behaviours that may include physical, sexual and psychological violence. IPV can also include threats of violence, physical harm, attacks against property or pets, as well as other acts of intimidation, harassment, economic abuse, emotional abuse, isolation and deprivation, and use of children as a means of control. While intimate partner violence can also occur from women towards men and also in same-sex relationships, intimate partner violence remains the most common form of male violence against women. By contrast, men are far more likely to experience violent acts by strangers or acquaintances, rather than by someone close to them[17]. Intimate partner violence jeopardizes women’s lives, bodies, psychological integrity and freedom and has been called the most pervasive yet least recognized human rights abuse in the world.

Domestic Violence[18]: All acts of physical, sexual, psychological or economic violence that occur within the family or domestic unit. The family/domestic unit refers to families of biological or legal family ties, former and current spouses or partners. It is also irrespective whether or not the person exercising the violence shares or has shared the same residence as the person experiencing the violence. Intimate partner violence is one aspect of domestic violence. Domestic violence can be exercised by any family member towards another family member, as long as they are all part of the same domestic unit.

Socio-economic violence: Any act of discrimination and/or denial of opportunities that leads to the prevention of the assertion and enjoyment of civil, social, economic, cultural and political rights. It includes restriction of access to education, health services or the labour market; restricting access to financial resources; denial of property rights; property damage; not complying with economic responsibilities, such as alimony; social exclusion/ostracism based on sexual orientation or acts considered inappropriate with regards to gender norms; tolerance of discriminatory practices; obstructive legislative practices; public or private hostility to LGBTIQ+ persons.

Harmful traditional practices[19]: Harmful traditional practices are forms of violence which are committed primarily against women and girls in certain communities and societies and are presented or considered as part of accepted cultural practice. These include:

Female genital mutilation: This involves the cutting of genital organs for non-medical reasons, usually done at a young age. The procedure ranges from partial or total cutting, to removal of part of the genitals and stitching of the genitals for cultural or non-therapeutic reasons. FGM is recognized internationally as a violation of the human rights of girls and women. It reflects deep-rooted inequality between the sexes, and constitutes an extreme form of discrimination against women. Because it is nearly always carried out on minors, it is also a violation of children’s rights. The practice also violates a person’s rights to health, security and physical integrity, the right to be free from torture and cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment, and the right to life when the procedure results in death (WHO, Key facts on FGM, 2018).

Early marriage: This refers to forced, coerced and arranged marriage of young girls under the age of legal consent. Sexual intercourse in such relationships constitutes statutory rape, as the girls are not legally competent to provide meaningful consent.

Forced marriage: Forced, coerced and arranged marriage against the person’s wishes, which is exposed to violent and/or abusive consequences if they refuse to comply. Forced marriages are almost always followed by expectations for having children, most often resulting in forced unplanned pregnancies.

Honour-based killing or maiming: Maiming (causing permanent injury to the body) or murdering a woman or a girl as a punishment for acts considered inappropriate with regards to her gender, and which are believed to bring shame on the family or community (i.e. for attempting to marry someone not chosen by the family, being raped, having an extra-marital affair, loss of virginity prior to marriage, conflicts regarding inheritance, refusing an arranged/forced marriage, homosexuality). Women are also killed to preserve the honour of the family (i.e. as a redemption for an offence committed by a male member of the family).

Denial of education for girls or women: Removing girls from school, prohibiting or obstructing access of girls and women to basic, technical, professional or scientific knowledge.

Structural and Institutional gender-based violence: Structural violence refers to the ways by which social inequalities and political-economic systems place particular persons or groups in situations of extreme vulnerability[20]. States and institutions condone and perpetrate sexual and gender-based violence when discriminatory practices are not challenged and prevented, including through the use of legal and policy instruments. Moreover, laws and institutionalized and governmental policies that systematically ignore or undermine the human rights of certain populations (LGBTIQ+ persons, migrants, people with disability, Roma, sex workers etc.) also constitute forms of institutionalized gender-based violence and enhance the vulnerability of these groups to SGBV. More specifically, specific examples of structural and institutional SGBV include:

- Restriction or refusal of services or stigmatization of certain vulnerable groups when trying to get services (health services, social welfare, asylum services, information provision etc.).

- Insensitivity by various institutions to promptly respond to SGBV and provide immediate care and protection to the person experiencing the violence (such as school’s slow or no response to gender-based or homophobic bullying, delayed responses by social services in cases of intimate partner violence, stalling by police to prosecute the person exercising the violence etc.).

- Exploitation and abuse by government officials or staff working at various institutions in the form of physical and psychological force or other means of coercion (threats, inducements, deception or extortion) with the aim of gaining sexual favours in exchange for services.

- Rape, sexual assault and sexual exploitation that takes place by armed forces in places of conflict.

- Police harassment, bias-motivated assaults and brutality towards LGBTIQ+ persons and sex workers expressed as being arbitrarily stopped, subjected to invasive body searches, unjustified detention, humiliation, physical assaults and sexual assaults. Trans people who engage in sex work are more than twice as likely to report physical assaults by police officers and four times as likely to report sexual assault by police.

- National laws that do not provide adequate safeguards against sexual and gender-based violence and discriminatory practices within the judicial and law enforcement bodies perpetrated SGBV with impunity

Femicide: The term femicide means the killing of women and girls on account of their gender, perpetrated or tolerated by both private and public actors. It covers, inter alia, the murder of a woman as a result of intimate partner violence, the torture and misogynistic slaying of women, the killing of women and girls in the name of so-called honour and other harmful-practice-related killings, the targeted killing of women and girls in the context of armed conflict, and cases of femicide connected with gangs, organized crime and trafficking[21]. Femicide stems from patriarchy, racism and stigmatization; women are killed because of hatred, contempt and a result of ownership. The most common form of femicide is the killing by an intimate partner as an escalation of intimate partner violence. Other forms of femicide also include honour-based femicide (killing a woman to preserve or restore the family’s honour), lesbophobic femicide (killing of women on the basis of their gender and her sexual orientation, which is a form of hate crime), trans femicide (killing of trans women as a form of hate-crime against trans persons) and the killing of sex workers. Deaths of women or girls due to harmful cultural practices (for instance due to complications after female genital mutilation, deaths of infants or young girls due to neglect) as also perceived as forms of femicide. Femicide is significantly undetected and underreported, since prosecutions usually do not integrate a gender perspective.

● 3.4. The complexities and escalation of violence

The iceberg model [22]

Violence sometimes starts with a ‘meaningless’ act which is often ignored. Individual acts of heteronormative/sexist/ homophobic/ transphobic/ interphobic and otherwise derogatory and hurtful language, ‘jokes’ or comments, may seem ‘benign’, harmless, even well-meaning and not aiming to hurt. Consequently, such language and behaviours are often bypassed in lieu of normalization: in the context of patriarchal norms, such behaviours are thought to be rational responses and ones that often seem ‘normal’ and ‘ justifiable’.

Taking a look at the picture of the iceberg below, we can see that while it is easier for us to recognize the more overt manifestations of violence such as murder, rape, sexual violence, physical abuse and verbal abuse, we often remain oblivious to the hurtful impact of the more covert manifestations of violence. Derogatory language or jokes, practices that render certain groups invisible, shaming, isolation and exclusion, among others, are practices that lay at the bottom of the iceberg, because they are not easily recognized as hurtful, racist and abusive. However, it is these practices that constitute an overall climate of disrespect of diversity and human rights violations and give rise to all the behaviours that lie at the visible part of the iceberg. Such behaviours, when put together as different parts of a puzzle over time, synthesize a vivid, powerful and coherent picture, that of sexism, homophobia, transphobia, biphobia, interphobia and gender-based and sexual violence in all its forms.

The common thread amongst these hurtful attitudes, beliefs and behaviours is the thread of hostile/hegemonic masculinity and patriarchal norms which overshadow and violate the rights, needs, dignity and safety of girls, women, people with SOGIESC diversities and all groups at risk of SGBV. Allowing these behaviours to go unnoticed and unaddressed as human rights violations, creates the impression that such types of violence can be tolerated, thus cultivating an environment which perpetuates inequality, discrimination, prejudice, abuse and oppression.

The more certain jokes, stereotypes, and normative perceptions about gender, gender roles, gender identities, gender expressions and sexual/romantic attractions are overlooked, the more they can brew intimidation, dominance, fear and insecurity. This leads not only to a culture of acceptance and the condoning of gender-based and sexual violence, but often creates a fruitful ground for violence to escalate from the most covert forms (jokes, comments, invisibility etc) to the most overt forms (physical harm, rape, sexual violence and murder).

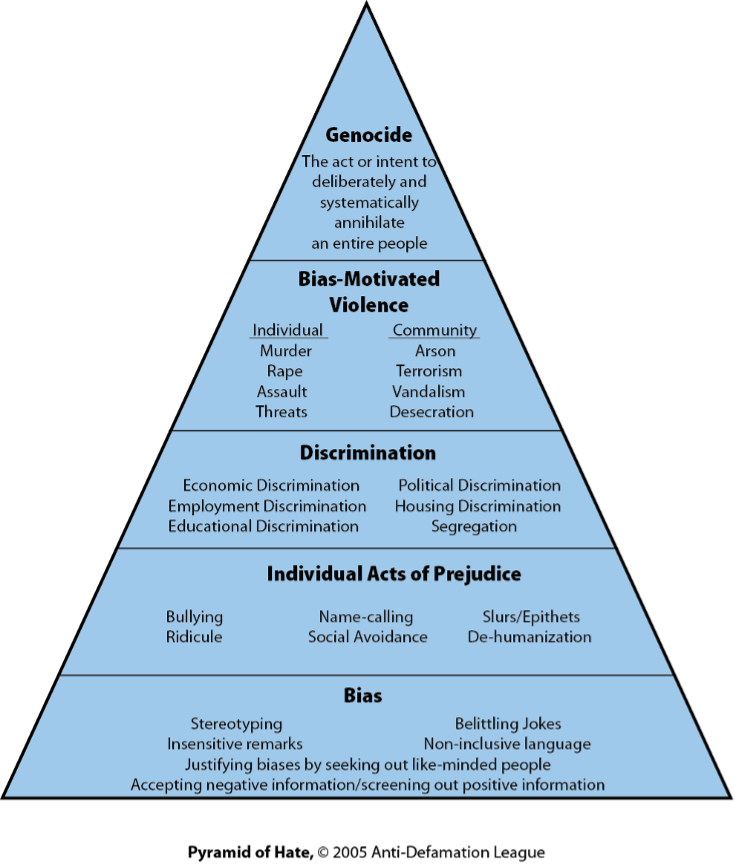

The Pyramid of Hate[23]

The Pyramid of Hate indicates how biased attitudes and behaviours can grow in complexity from the bottom to the top. The pyramid suggests that biased attitudes such as stereotypes, not inclusive language and derogatory remarks grow into individual acts of prejudice such as bullying, name calling, isolation and social distance. Prejudice turns into discrimination, which means the exclusion of a person from access and control, of resources (such as economic, political, social, educational, access to justice). Discrimination can take place both at an individual level (i.e. not hiring a trans person because they are trans) and an institutional level (discriminatory laws and practices, for instance denying access to healthcare to a sex worker). Moving up from discrimination, in the upper levels of the pyramid, we have bias motivated violence, including physical violence, assault, rape and murder. The upper most level of hate is genocide, whereby intentionally and deliberately an entire group of people (e.g. national/ethnic/religious group etc.) is annihilated.

Although behaviours at each level negatively impact individuals and groups, as we move to the upper levels of the pyramid, the behaviours have more life-threatening consequences. Like a pyramid, the upper levels are supported by the lower levels. In this respect, violent behaviours are supported by prejudice, discrimination and attitudes of bias. If behaviours on the lower levels (stereotypes, prejudice, non-inclusive language, bullying, social distance, discrimination etc.) are normalized or are considered acceptable, this would in turn result in the behaviours at the next level becoming more accepted.

● 3.5. Incidence and extent of SGBV

Some worldwide statistics on SGBV[24]:

- 35% of women worldwide are estimated to have experienced at some point in their lives either physical and/or sexual intimate partner violence or sexual violence by a non-partner. In some countries, this figure goes up to 70%.

- Worldwide, more than 700 million women alive today were married as children. Of those women, more than 1 in 3—or some 250 million—were married before the age of 15.

- About 70% of all human trafficking victims detected globally are women and girls.

- At least 200 million women and girls alive today have undergone female genital mutilation/cutting in 30 countries. While this figure is difficult to estimate in Europe, the European Institute of Gender Equality (EIGE) has made an attempt to estimate the extent of FGM in Europe in their report “Estimation of girls at risk of female genital mutilation in the European Union[25]”. France and the UK indicate a high number of women/girls who have already experienced some form of FGM while the risk for experiencing FGM while seeking asylum or refugee status in Europe still stands extremely high is some countries (over 70%).

- Around 120 million girls worldwide (over 1 in 10) have experienced forced intercourse or other forced sexual acts. By far the most common perpetrators of sexual violence against girls are current or former husbands, partners or boyfriends.

- A total of 87,000 women were intentionally killed in 2017[26]. More than half of them (58 per cent) ̶ 50,000 ̶ were killed by intimate partners or family members, meaning that 137 women across the world are killed by a member of their own family every day. More than a third (30,000) of the women intentionally killed in 2017 were killed by their current or former intimate partner ̶ someone they would normally expect to trust.

The situation in Europe:

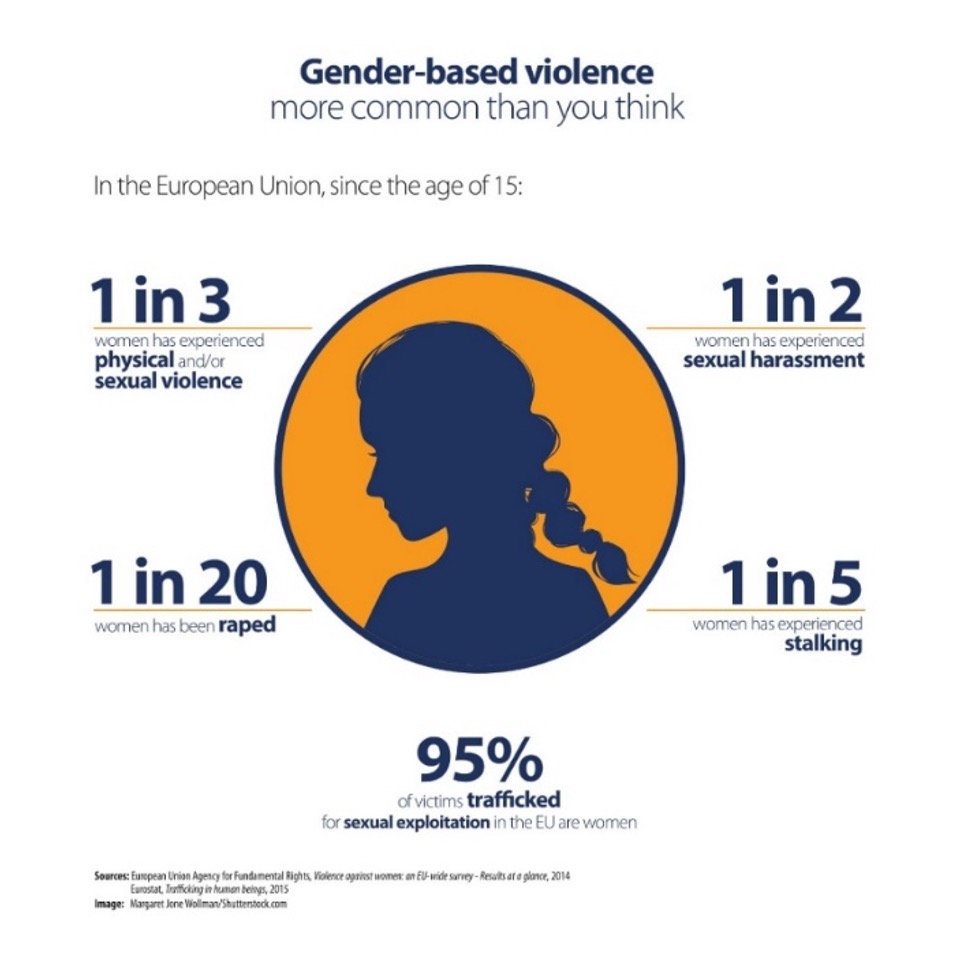

- According to the survey of the European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights (FRA, 2014) 22% of women in the EU have experienced physical and or sexual violence from a partner since the age of 15. It is also estimated that, in the last 12 months[27] in the EU, 13 million women in have experienced physical violence and an estimated 3.7 million women have experienced sexual violence.

- Moreover, one in three women (32 %) has experienced psychologically and emotionally abusive behaviour by an intimate partner, either by her current partner or a previous partner. A high share of women, 18%, has also experienced stalking since the age of 15. 21 % of the women who were stalked, mentioned that the stalking lasted more than two years.

- UNODOC (2018) estimates that around 3,000 women were killed in the EU (28) by an intimate partner or family member in 2017.

- Sexual harassment is also high, with every second woman (55 %) in the EU having experienced sexual harassment at least once since the age of 15. Overall, 1 in 10 women have experienced sexual abuse, 1 in 20 women (5%) have experienced rape and a similar percentage have experienced attempted rape (6%) from a partner or a non-partner. The split between partner and non-partner as the person who exercises sexual violence stands at 65% vs. 35% respectively for rape and 55% vs. 45% for attempted rape.

Statistics on discrimination and violence against LGBTIQ+ persons

According to the EU LGBT survey (2017)[28], lesbian, gay, bisexual and trans (LGBT) persons face various obstacles to enjoying their fundamental rights. LGBTIQ+ individuals experience discrimination in various areas of life, and in particular employment and education. Many have also experienced violence and harassment, frequently in public places. Specifically, according to the EU LGBT survey:

- Almost half of all respondents (47 %) say that they felt personally discriminated against or harassed on the grounds of sexual orientation in the year preceding the survey. Lesbian women (55 %), respondents in the youngest age group between 18 and 24 years old (57 %) and those with the lowest incomes (52 %) experience the highest discrimination.

- Figures for physical abuse are also high: a quarter (26 %) of all LGBT respondents indicate that they were physically or sexually attacked or threatened with violence in the previous five years

- One in five (20 %) of LGB persons who were employed and/or looking for a job experienced discrimination at work. This figure rises to 29% among trans people who are employed.

- Similarly, 18% mention to have felt discriminated at school and more than two thirds (67 %) hid or disguised the fact that they were LGBT during their schooling before the age of 18, out of fear of discrimination

- Discrimination at healthcare institutions stands at 12% among LGB individuals. Trans people are more vulnerable to discrimination in the area of health, with 1 in 5 (20%) claiming such experiences.

● 3.6. Impact of SGBV[29]

The impact of SGBV is devastating for both for the people who are experiencing it and their communities. SGBV can lead to debilitating and long-term trauma, which in turn effects the person’s physical and psychological health, often leads to psycho-social problems and greatly impacts the person’s feeling of security and safety.

Physical injuries, chronic pain, somatic complains, paralysis, disability, eating disorders, sleep disorders, infections (including STIs and HIV), unwanted pregnancies, pregnancy complications, menstrual and gynaecological disorders and substance abuse are amongst the most common effects of SGBV in physical health. The most extreme consequences in this respect include death (either by femicide or suicide), maternal mortality, infant mortality and AIDS-related mortality.

The impact on psychological health is also severe including chronic anxiety, depression, mental illness, post-traumatic stress, self-hate, self-blame, disempowerment, feelings of loss of control over their own life, low self-esteem and suicidal thoughts and behaviour. Because of the impact on their self-esteem, people who experience SGBV may end up replicating patterns of victimization in future relationships, which condemns them to a recurrent cycle of violence. Perhaps the most prominent impact of SGBV on psychological health is on the feeling of safety and security. People who experience SGBV report feeling insecure, unsafe, afraid and unprotected.

Victim-blaming attitudes result in social stigma, social rejection, isolation and estrangement. As a result of the fear of social stigma, many people who experience SGBV avoid reporting it or are resistant to ask for help. Social stigma/rejection not only results in further emotional damage (including shame, self-hate and depression) but it increases survivors’ vulnerability to further abuse and exploitation[30]. In return, this increases the risk to poverty which again acts as an extra layer of vulnerability for abuse.

Victim-blaming attitudes are also reflected in institutions (such as the police, judicial systems, the health and education sectors) which may refuse to provide services, or which may fail to protect the people who are experiencing SGBV. If institutions are not sensitive to the needs for immediate care, protection, dignity and respect, further harm and trauma may result because of delayed assistance or insensitive behaviour. Community attitudes of blaming the person who experiences the violence are also reflected in the courts. Many sexual and gender-based crimes are dismissed or punished with light sentences. In some countries, the punishment meted out to people exercising the violence constitutes another violation of the survivor’s rights and freedoms, such as in cases of forced marriage. The emotional damage to people experiencing violence is compounded by the implication that their abuser is not at fault.

- unhcr.org/sexual-and-gender-based-violence.html

- Definitions adapted from the publication: “Sexual and Gender-Based Violence against Refugees, Returnees and Internally Displaced Persons” UNHCR, May 2003 , https://www.unhcr.org/protection/women/3f696bcc4/sexual-gender-based-violence-against-refugees-returnees-internally-displaced.html

- Adapted from EIGE’s definition of GBV. https://eige.europa.eu/gender-based-violence/forms-of-violence

- https://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Issues/Women/WRGS/OnePagers/Sexual_and_gender-based_violence.pdf

- Adapted from The New Humanitarian: Journalism in the times of crisis http://www.thenewhumanitarian.org/feature/2004/09/01/definitions-sexual-and-gender-based-violence

- Adapted from “Sexual and Gender-Based Violence against Refugees, Returnees and Internally Displaced Persons” UNHCR, May 2003 , https://www.unhcr.org/protection/women/3f696bcc4/sexual-gender-based-violence-against-refugees-returnees-internally-displaced.html

- EIGE definition: https://eige.europa.eu/thesaurus/terms/1657

- Definition from the Council of Australian Governments’ National Plan to Reduce Violence against Women and their Children 2010–2022. https://plan4womenssafety.dss.gov.au/

- UNHCR (2003). Sexual and Gender-Based Violence against Refugees, Returnees and Internally Displaced Persons. Can be downloaded at: https://www.unhcr.org/protection/women/3f696bcc4/sexual-gender-based-violence-against-refugees-returnees-internally-displaced.html

- Adapted from the ‘The Gender Ed Educational Program-Teachers Guide: Combating Stereotypes in Education and Career Guidance. Mediterranean Institute of Gender Studies (2018)

- Adapted from the Manual: ‘Gender-based Violence Training Manual. Restless Development Sierra Leone is the youth-led development agency (2013)’

- (de Benedictis et al., 2006, p. 2).

- (de Benedictis et al., 2006, p. 3)

- Rainbow families refer to same-sex or LGBTIQ+ parented families, i.e. to parents who define themselves as LGBTIQ+ and have a child (or children) , are planning to have a child (either by adoption, surrogacy or donor insemination etc) or are co-parenting

- https://web.archive.org/web/20051126153146/http://www.homeoffice.gov.uk/crime-victims/reducing-crime/hate-crime/

- Definition in: Minnesota Advocates for Human Rights, 2003, p. 1

- Heise L, Garcia Moreno C. Violence by intimate partners. In: Krug EG et al., eds. World report on violence and health. Geneva, World Health Organization, 2002:87– 121

- EIGE Glossary definition

- Source: The New Humanitarian http://www.thenewhumanitarian.org/feature/2004/09/01/definitions-sexual-and-gender-based-violence

- Padilla et. al (2007). Globalization, Structural Violence, and LGBT Health: A Cross-Cultural Perspective.

- Source: EIGE’s (2017) Gender Equality Glossary definition of femicide

- Adapted from Council of Europe’s campaign: Sexism: Name it, see it, stop it. https://www.coe.int/en/web/human-rights-channel/stop-sexism

- The Pyramid of Hate was developed by the Anti-Defamation League as part of its curriculum for its A WORLD OF DIFFERENCE® Institute.

- https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/MEMO_17_3222

- https://eige.europa.eu/publications/estimation-girls-risk-female-genital-mutilation-european-union-report

- UNODOC (2018). Global study on homicide: Gender related killing of women and girls.

- During 2012

- https://fra.europa.eu/sites/default/files/fra-eu-lgbt-survey-main-results_tk3113640enc_1.pdf

- Adapted from UNHCR’s report on Sexual and Gender-Based Violence against Refugees, Returnees and Internally Displaced Persons (2003).

- UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs: https://www.unocha.org/story/sexual-and-gender-based-violence-time-act-now