● 8.1. Theoretical background

Sex, Gender and Gender identity

Sex is a label that children are assigned at birth, based on their (perceived) body anatomy (genitals) and the general physiology of their body (e.g. hormones, chromosomes). The biological differences and the biological “reality” into which we are born, leads to our first categorization as “male” or “female” and often goes on our birth certificate. As soon as a child is born, the sex is assigned: we know if it is a ‘boy’ or a ‘girl’ based on whether it is perceived to have a penis or a vagina.

Sex characteristics refer to biological and physical traits of a person which are indicative of the biological sex. The primary sex characteristics include the sex chromosomes (XX , XY or other variations), the anatomy of the external genitalia (e.g. penis, testicles, vulva, labia etc.), the anatomy of internal genitalia (clitoris, vagina, uterus, seminal glands, prostate etc.) and the levels of sex hormones (oestrogen, testosterone). Secondary sex characteristics develop at puberty and generally include body shape (‘hour-glass’ figure vs. ‘triangle’ figure), pelvis width, shoulders’ width, breast and muscle development, hair and fat distribution in the body and voice (usually the voice breaks in young males). Even though sex characteristics are used to ‘define’ biological sex, it is important to remember that not all people are cisgender (cisgender is a person whose sense of personal identity and gender corresponds with the sex assigned at birth). People with stereotypical male sex characteristics may define themselves as female, trans or as nonbinary for instance. Equally, stereotypical female sex characteristics may create the impression that the person is a woman, but this person may define themselves as male, queer, androgynous, nonbinary, gender fluid or anywhere on the gender spectrum that feels right for them.

Intersex: The biological ‘realities’ into which we are born, and are often used to categorize us as males or females (binary sex interpretation) are not the same for everyone. About 1.5% of people are ’intersex[1]’ (as common as people with red hair) which means they have physical, hormonal or genetic features that don’t seem to fit the typical definitions of female or male. There are many different intersex variations. For example, a person might be born appearing to be female on the outside, but having mostly male-typical anatomy on the inside and vice-versa. Some people are born with what looks like totally male or totally female genitals, but their internal organs or levels of hormones released during puberty don’t match. Other intersex people are born with genitalia or internal sex organs outside of the typical male/female binary, such as having both ovarian and testicular tissues, having a noticeably large clitoris and no vaginal opening or having a notably small penis and a scrotum that is divided so that it looks more like labia[2]. In some intersex persons, sex chromosomes and body anatomy may not align the way one would expect. Other intersex people have a combination of chromosomes that is different than XY (male) and XX (female), such as XXY, or are born with mosaic genetics, so that some of their cells have XX chromosomes and some cells have XY[3]. Anatomy can be entirely different for one intersex person as compared to another, thus intersexuality is actually a spectrum and not a single category.

Gender: Gender refers to the set of expectations and rules that we, as society, have of how men and women are supposed to act, dress, behave, look like and so on. Gender includes a set of cultural identities, expressions and roles that are socially assigned— to define what is feminine or masculine — based on the interpretation of a person’s biological sex[4]. These “unwritten” rules of society are referred to as the gender norms. Butler (1990) claims that gender is only but a cultural creation: it is not something we “have”, nor is it a “thing”, but it is the performance of a role. Therefore, in our everyday lives we play the part of a gender which is performed in specific historical, cultural, social and political contexts.

Gender is learned through socialization and is internalized by all members of a society, with most people trying to conform to societal expectations and the gender norms. Gender can also refer to someone’s perception of oneself or one’s experience. Therefore, it can be a personal but also a social and political label[5].

Gender also shapes the privileges and opportunities associated with being male and female and the relationships between women and men and girls and boys, as well as the relations amongst women and those amongst men[6]. Gender carries a hierarchy: unequal power structures related to gender, place women and people who may not conform to traditional gender norms at a disadvantage. Through patriarchal structures men have traditionally enjoyed more power and more privileges than women. Similarly, gay, trans and men from ethnic minorities are considered to be lower in the social hierarchy, because they do not ‘fit’ the stereotypical model of masculinity.

Gender norms are well engrained in society and lead to the development of the ideal standard of masculinity and femininity, which may not represent reality, but constitutes the dominant model for “evaluating” a man or a woman, embedding the binary representation of gender further. Messages about femininity and masculinity are embedded in advertising, media, news, educational materials, political and public discourse. These messages are largely based on gender stereotypes, which even though are widely understood as generalizations and as applicable to a large majority of people, still largely shape our perceptions about gender. Nowadays, we refer to masculinity not as a fixed identity, but as a set of practices which may differ according to the social and political context of a specific era (Connell and Messerschmidt, 2005). In every society, however, there is a “dominant” model of masculinity, “hegemonic masculinity”,which may not represent the majority of men, but it does constitute the main benchmark for how masculinity should be expressed in a specific society[7]. In most western societies, according to the dominant model of masculinity, men are expected to be strong, tough, muscular, sexually active, clearly and strongly heterosexual, powerful, authoritative, protective, have emotional self-restraint, be the decision-makers, be in control and so forth. In a similar manner, we refer to the notion of “femininities”, a notion which encompasses all the rules and practices that define the “right” or ‘proper’ appearance and behaviour a woman needs to display, depending on a specific time and culture. Femininity is often defined by a woman’s adherence to the dominant standards of beauty, her ability to please, her capacity to self-sacrifice and her nurturing of her family[8]. Girls and women are also expected to take on the role of the “caregiver”, look after the household and the children, be shy, dress modestly, be more passive in comparison to men and exercise control over their sexuality.

The viewing of gender as consisting of only two separate categories, ‘masculine’ or ‘feminine’, is called the gender binary. In reality, however, gender identities lie on a spectrum and a person can identify themselves outside the gender binary. People who do not identify as neither exclusively male nor female often identify as nonbinary and may not conform to traditional gender roles, acting and expressing themselves in a non-stereotypical manner and/or a gender-neutral way across a spectrum of gender identities. In some cases nonbinary people can still fit within what society deems cisgender and traditional or appear to do so. Nonbinary is an umbrella term and nonbinary people may describe themselves using one or more of a wide variety of terms (such as queer, gender neutral, gender queer, gender fluid, gender non-conforming, agender, bigender etc.). Individuals who identify as nonbinary may opt to use the pronouns they/them (instead of she/he, her/his) for themselves or ze, sie, hir or may use no pronoun at all.

Gender identity refers to how person deeply feels and experiences their gender, which may or may not correspond with the sex assigned at birth. Gender identity also pertains to the personal sense of one’s body and a person’s gender expression (i.e. how they express their gender, including physical appearance, clothing, accessories, speech and mannerisms). There is a great diversity of gender identities as people’s personal sense of self differ. There is no set of rules to how people can define themselves and each person’s experience of their gender identity is unique While some people identify as female or male, others may identify as nonbinary, trans, agender, gender fluid, queer, bigender, pangender, questioning etc. The name and pronouns are an important part of a person’s identity; thus, it is important to respect how a person chooses to be called. Gender identity is not the same as sexual orientation, and people of a certain gender identity (female, male, nonbinary, trans, queer etc.) can have any sexual orientation (heterosexual, gay, lesbian, bisexual, asexual, pansexual etc.).

Queer An umbrella term that is inclusive of people who are not straight and/or cisgender. It is used as broad term for individuals to describe a sexual orientation, gender identity or gender expression that does not conform to dominant societal norms. Even though in the past it was used as a derogatory term for LGBTIQ+ people, today many within the LGBTIQ+ community identify as queer and have reclaimed this term as an affirming word/identity. Queer also has political contexts for some individuals who use it.

Questioning: Describes a person who is unsure of or is questioning their sexual orientation and/or gender identity before labelling themselves as LGBTIQ+, straight or any other identity.

Trans: Trans describes many diverse groups who all in some way encompasses any gender identity that may challenge or may not conform to the sex and gender attribution system as well as may not conform to the gender binary system (male/female).

Transgender is an umbrella term that encompasses many definitions of gender identity and gender expression of persons who experience a deep sense of identification with a gender different from the sex assigned to them at birth. It is estimated that anywhere between 2-6% of boys and 5-12% of girls identify or express their gender differently from their binary sex /gender assigned at birth (Moller, Schreier, Li, & Romer, 2009). This can be expressed in many different ways; through gender expression, clothing, appearance, by taking hormones, having surgeries, changing their names, using specific pronouns, and so on[9]. Some transgender individuals feel a strong sense of the opposite gender identity than the one they were assigned at birth (i.e. assigned female at birth but having a clear and strong male identity) and define themselves within the binary, as men or women (or transmen/transwomen). It is important to remember that transgender persons express their gender identity in many different ways and not all of them undergo surgery or hormonal therapy, either because they consciously choose not to or because they are not able to due to monetary or medical constrains.

Transsexual: Transsexual refers to people whose gender identity differs from the sex assigned to them at birth and decide to undergo bodily modification (such using hormones or having sex reassignment surgery), so that their physical bodies correspond to their felt gender identity.

| Notably, transsexual and transgender remain controversial words: generally speaking the consensus is that the usage of these words is quite divisive and pathologizing due to their background in the clinical context. It can be quite objectifying for trans people to focus their existence and identity on their genitals and the procedures they have undergone. Some may even consider these words as derogatory and don’t identify with them at all. As such, the word ‘trans’ is a more inclusive term, encompassing those who identify as transgender or transsexual and those who don’t. |

Cross-dressing (previously mentioned as transvestite, which is considered a derogatory and offensive term) : dressing with clothes of a different gender from time to time for pleasure. Differently to trans individuals “cross-dressers,” do not necessarily identify with a gender different from the gender associated with the sex assigned to them at birth.

Diversity in SOGIESC: diversity related to Sexual Orientation, Gender Identities/Expressions and Sex Characteristics

Heteronormativity: is the belief that heterosexual relationships and traditional gender identities/gender roles are the “norm”, are deemed ‘natural’ and act as a reference point against which a society measures the humanness of everyone, thus exclusion is the natural outcome to any other type of gender or sexual diversity. Heteronormative beliefs assume that everyone adheres to the stereotypical ‘models’ of masculinity and femininity, is straight (unless otherwise stated), builds relationships with the ‘opposite’ sex, develops long-term, monogamous relationships, gets married, has children and so on. Heteronormativity, thus, acts as a system that normalizes behaviours and societal expectations that are tied to the presumption of heterosexuality and stick to a strict gender binary – consequently all other gender and sexual diversity should be made invisible and marginalized (Chase and Ressler, 2009). If people do not conform or dare to break the rules of this norm, they will often experience negative attitudes, prejudice, discrimination and violence. Heteronormativity provides the “social backdrop” for homophobic, biphobic and transphobic prejudices, violence and discrimination – the entire pyramid of hate is essentially based on heteronormative beliefs. Consequently, to protect themselves from the discrimination and harmful behaviours experienced in most spheres of life, many people are forced to hide their sexual orientation and/or gender identity.

Homonormativity: focuses only on the gay and lesbian identity and all other LGBTIQ+ identities such as bisexuality, polysexuality, pansexuality, asexuality, trans, nonbinary, intersex, questioning etc. are considered too complex, too specific and are made invisible.

Cisnormativity: The assumption that all human beings are cisgender, i.e. have a gender identity which matches their biological sex.

Heterosexism refers to the discrimination or prejudice against people of diverse sexual orientations on the assumption that heterosexuality is the ‘normal’ sexual orientation and is considered superior to lesbian, gay, bi, trans, intersexual, asexual, etc. . Heterosexism expresses a clear sense of superiority and it is also used for societies/cultures which favour heterosexuality and oppress non-heterosexual people when the motivation is clearly the idea of one being superior to the other[10].

Rainbow families refer to same-sex parented families or parents with diverse sexual orientations, gender identities and expressions or sex characteristics who have a child (or children), are planning to have a child (either by adoption, surrogacy or donor insemination etc.) or are co-parenting.

Gender stereotyping in (online) media and advertising

Media, online and offline, and advertising have a strong and unquestionable impact in influencing young people’s perceptions, understandings, beliefs and attitudes with regards to gender, identities, self-concept and relationships. TV, print ads, online messages, selfies, likes, posts, comments etc. give out explicit or implicit messages about gender, identities, body image, sexuality and relationships, reinforcing for the most part stereotypical norms and heteronormative perceptions. The sexualization of human bodies and particularly portraying women as sex objects has been a core marketing ‘strategy’ to sell any type of product, from water to clothes. Moreover, social networking sites largely act as a commoditized environment for flirting and search of partners.

Gender identities are primarily depicted within the binary, and relationships are presented within the sphere of heterosexuality, silencing and obscuring any diversity. Instagram selfies for instance are focused on mainstream representations of beauty, body image and appearance. Body shaming is also common. In terms of the male identity, more emphasis in social media is placed on the ‘macho’ persona, presenting men as being tough, strong, athletic (in basketball/football jerseys), aggressive and sexual ‘predators’. On the other hand, most stereotypical representations of girls are of them as sexualized objects, who are attractive, part of the party scene and seeking male attention. The sexual objectification of women is dangerous as it robs them of any personality traits and diminishes them to objects, suggesting that one can easily have power over them, condoning in this way sexual violence. Moreover, girls are much more likely than boys to be harshly judged for their degree of publicness in their online profiles. According to Bailey et al., 2013, girls who have an open profile, too many friends, or who post too much information about themselves run high risk of being called ‘sluts’ and all the psychological abuse that comes with that. These discriminatory standards however may hinder girls’ full online participation and may complicate their ability to participate in defiant gender performances.

These messages and depictions of gender norms greatly influence young people who are in the process of developing their identity and shape their views about the roles and opportunities they see available depending on their gender or sexual diversity[11].

On the counterpart, the cyberspace also provides the ‘space’ or the ‘forum’ for LGBTIQ+ individuals to circulate alternative perspectives to identity development. Self-reflective, personal stories of coming out may empower young people to embrace their sexual orientation. Similarly, trans YouTubers chronicling their everyday lives make way for others to claim a trans identity while providing healthy representations of trans people which correct discriminatory or abusive media depictions (Raun, 2014). Non-heterosexual flirting, discussions of diverse sexual fantasies in chat rooms and depictions of non-heteronormative couples normalize the diversity of sexual orientations and relationships. This new range of discourses (addressed to other LGBTIQ+ people as well as heterosexual and cisgender individuals) can have a prominent influence in creating new understandings of sexuality and gender (Duguay, 2016). Towards this end, these online depictions, posts, blogs, and videos can be used as tools in a training environment to challenge existing norms and heteronormative perceptions.

The spectrum of sexual orientation

Sexual orientation describes the emotional, romantic and/or sexual attraction a person feels towards another person or persons. Sexual orientation also lies on a spectrum and there are many different ways in which a person can define their sexual orientation. Some commonly recognized types of sexual orientation include heterosexual (people attracted to a different gender, usually women attracted to men and vice-versa), homosexual (attracted to the same gender identity), gay (men attracted to other men), lesbian (women attracted to other women), bisexual (attracted to two genders), polysexual (attracted to many gender identities) and pan sexual (attracted to all gender identities) Some people may only experience a romantic/emotional attraction, without experiencing a sexual attraction and define themselves as asexual.

Because sexual orientation is a spectrum, it is important to remember that people may define their sexual orientation outside labels, in a way that feels comfortable for them. For instance, there are people who may not define themselves as exclusively heterosexual or exclusively homosexual for instance, others who define themselves as heterosexual but choose to have sexual experiences with the same gender or others who may decide not to identify themselves with a particular sexual orientation at all. Sexual orientation is a part of the identity of a person that is self-determined as it is experienced, internalized and understood by the person themselves. It is something completely personal and individual to each person and it needs to be respected as such, without expectations of others to conform to labels that society considers ‘acceptable’ or ‘understands’ better.

Romantic orientation reflects our intrinsic desire to engage in romantic connections with others. A person may have romantic desire or attraction, but not experience sexual attraction, or vice versa (e.g. hetero-romantic asexual, aromantic bisexual).

Sexual identity: Sexual identity is complex because it is formed on multiple continuums. The three integral components of sexual identity are gender identity, sexual orientation and romantic orientation. While each of these aspects of ourselves exists independently on its own spectrum, to form our sexual identity, the three components also interact, encompassing in this way infinite and variable possibilities in which we can experience, embody and express our sexual identity.

Looking at the ways these three components of sexual identity intersect can be confusing or overwhelming. However, it is important to recognize that there are limitless possibilities and that all are natural expressions of human sexuality. The more we discuss gender and sexual identity, the more our understanding grows as to the many other self-determined identities we may not have considered in the past. As this is an ongoing process, it is important to respect and affirm ways that people self-identify, even if it is something we may not never heard of before or are even having difficulty to understand.

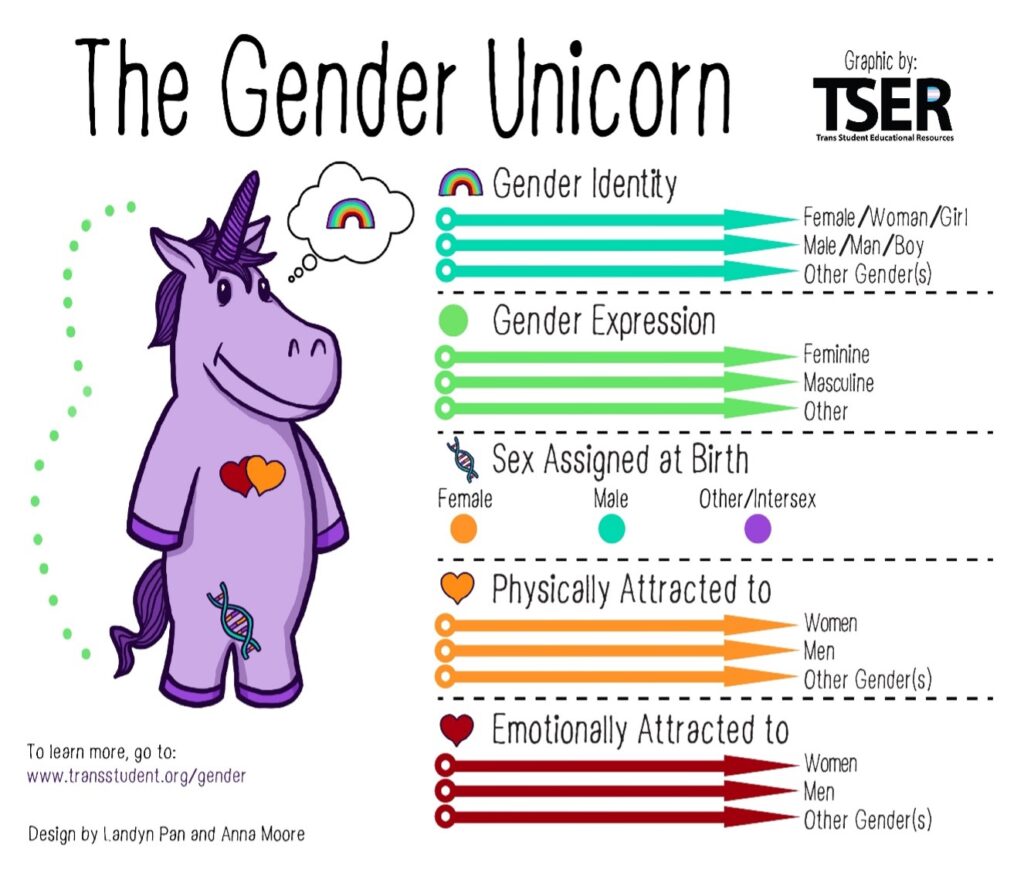

Putting it all together: sex assigned at birth, gender identity, gender expression, romantic and physical attraction

Acceptance and Inclusion of diversity related to SOGIESC (Sexual Orientation, Gender Identities/Expressions and Sex Characteristics

The first step to acceptance and inclusion of different identities related to gender and sexual orientation, is to remember that ‘labels’ (i.e. boy, girl, queer, intersex, lesbian, asexual etc.) can only serve as starting points for conversation, as no single word can encapsulate the entire diversity, complexity and multi-faced depth of a person. All people also have various intersecting identities that only scratch the surface of who they are.

Young people with diverse sexual orientations, gender identities/expressions and sex characteristics (SOGIESC) feel included and accepted when they can identify and express this diversity openly, visibly, freely and safely, without experiencing any form of violence, discrimination or hatred. Recognizing the multiple aspects of identity for any young person, means creating an environment where young people:

- have supporting conditions that allow them to fully express their identity and make full use of their abilities, reaching their outmost potential

- are encouraged and have real opportunities to express themselves without limitations, develop leadership skills, take initiatives and participate fully in their communities (school, circles of friends, neighbourhoods, ethnic communities etc.)

- have a sense of ‘belonging’ and feel that they are visible, have a voice and this voice is heard

- feel safe, recognized, respected, celebrated and are positively categorized

To create a safe and supportive environment that embraces diversity in terms of sexual orientations, gender identities/expressions and sex characteristics, young people

- understand how norms work and are especially aware of all the hidden and implicit forms of heteronormative thinking, perceptions, stances and images

- make conscious efforts to challenge these norms, both in the offline and online worlds

- consciously try to make no assumptions about a person’s gender, sexual orientation or sex characteristics

- respect the pronouns and the names other people want to use for themselves

- use inclusive language when they speak of/about others that makes no assumptions about a person’s gender, partner, family situation or relationship status (not all people are male or female, date the ‘opposite’ sex, have a penis or a vagina, have a male and female parent, are in a long-term monogamous relationship etc.)

- handle disclosures of coming out or disclosures concerning gender identity with understanding, openness, active listening, acceptance, empathy and confidentiality

- stand up to homophobic, biphobic, interphobic and transphobic bullying in their schools

- support and empower other young people who have experienced sexual and gender-based violence to seek support and break the cycle of abuse.

● 8.2. Non-formal education activities on sex, gender, gender identities/expressions and sexual diversity

● 8.3. Links to additional resources and information

IGLYO: The International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer & Intersex (LGBTIQ+) Youth and Student Organisation, https://www.iglyo.com/

ILGA: The International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Association, https://ilga.org/

Trans Students Educational Resources: https://transstudent.org/

GLSEN Education Network: https://www.glsen.org/

GALE, the Global Alliance for LGBT Education: https://www.gale.info

A Guide to Gender: A social advocates handbook, 2nd edition. Sam Killermann (2017). Austin, Texas: Impetus Books. http://www.guidetogender.com/

The Gender book: https://thegenderbook.com/the-gender-booklet

Norm criticism toolkit. IGLYO (2015). Can be downloaded at: https://www.iglyo.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/Norm-Toolkit-WEB.pdf

The Safe Zone project: https://thesafezoneproject.com/

- Fausto-Sterling, Anne (2000). Sexing the Body: Gender Politics and the Construction of Sexuality. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 0-465-07713-7.

- https://isna.org/faq/what_is_intersex/

- https://isna.org/faq/what_is_intersex/

- Council of Europe (2018): Safe at school: Education sector responses to violence based on sexual orientation, gender identity/expression or sex characteristics in Europe

- IGLYO (2016). Norm criticism toolkit

- EIGE definition of gender: https://eige.europa.eu/gender-mainstreaming/concepts-and-definitions

- The Gender Ed Educational Program-Teachers Guide: Combating Stereotypes in Education and Career Guidance. Mediterranean Institute of Gender Studies (2018)

- The Gender Ed Educational Program-Teachers Guide: Combating Stereotypes in Education and Career Guidance. Mediterranean Institute of Gender Studies (2018)

- IGLYO (2016). Norm Criticism Toolkit

- https://takemehomefromnarnia.tumblr.com/post/55954823709/heterosexism-homophobia-and-heteronormativity

- Maltese Safer Internet Centre Report, 2019. https://www.betterinternetforkids.eu